A set of precious books sits in the office of associate professor J.B. Mayo. Two are red leather-bound social studies textbooks from the early 1950s. Another is a fragile, brown logic textbook, dated 1891. The books belonged to Mayo’s great-grandfather, Charles Franklin Simpson, first in an academic lineage of four generations.

Mayo never knew his great-grandfather but became interested in social studies as a kid.

“In my house it was just standard that we would watch the news,” he says of his childhood in Virginia. “Every night at 6:30, it was normal to not talk because of the news.” Watching the PBS series Eyes on the Prize was especially memorable.

Mayo taught in Virginia schools for more than seven years before moving to the University of South Florida to complete a Ph.D. in education. He arrived in Minnesota for postdoctoral work in 2005. As a faculty member in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction today, Mayo’s area is social studies education.

“I prepare teachers,” Mayo says. “I teach them how to teach with an equity mindset.” He calls methods courses the bread and butter of his work, specifically pedagogies for teaching social studies.

Diversity and democracy

Mayo also pursues a full line of research. One of the leading topics is how to bring LGBT/queer histories—the histories of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons and communities—into the field. He seeks to help teachers find ways to make that content part of their regular teaching.

He also researches and writes about school genders-and-sexualities alliances, or GSAs. In schools with GSAs, he has found, students are more open to the idea that there are multiple expressions of gender, and there is more acceptance of various sexual orientations and of difference.

“There is still bullying going on—that hasn’t been solved,” he says. “But where there are GSAs, the issues that queer students face are far decreased.”

Students in GSA schools are more aware of their language, he has found. For example, the phrase That’s so gay has been eradicated at a school with a GSA where Mayo conducted a major research project.

For the past three years he has been working with Independent School District 622 – Maplewood-North St. Paul-Oakdale as part of their Equity Team. Mayo is helping their GSAs while also working with affinity groups across the district. This is the first time he has worked at the middle school level with GSAs as previous work was with high schools. Students as young as 11 years old are openly discussing difference among genders and learning to understand that gender is fluid and socially constructed instead of binary, that young people and adults are able to express their genders in multiple ways, and it is really okay to express oneself in these ways.

“Folks have been valuing this difference for thousands of years. Why can’t we accept it now?”

A new area of research for Mayo since coming to Minnesota centers on “Two Spirit” people among American Indian communities. Though nations such as the Navajo have recognized the concept of gender variance for centuries, Two Spirit is a relatively new term that encompasses the idea of one person embodying both the masculine and the feminine spirit simultaneously.

“This has been seen as a gift,” Mayo says. “You had a special place in society because you had this endowment of both spirits. For the Navajo, there are not just two genders but six!”

Mayo is exploring the historic and changing place of Two Spirit people within their communities, and writing curriculum that honors their contributions. He is currently working with a former student and co-teaching a social studies unit, Social Identity, Personality, and Gender, at Forest Lake High School.

“I try to give simple lessons that we don’t have to destroy difference, we don’t have to bully difference,” he says. “It can be appreciated, it can be exalted, and people who are different can be productive members of society. Folks have been valuing this difference for thousands of years. Why can’t we accept it now?”

At the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Mayo is coordinating the Teacher-Scholars of Color Program which is open to all teacher candidates of color in the College’s post-bac (initial licensure) programs. The program provides resources, mentorship, and networking opportunities to attract and retain teacher candidates of color.

In 2016, the University recognized Mayo’s dedication to equity and social justice in schools with the Josie Johnson Human Rights and Social Justice Award. Colleagues noted, in particular, his scholarship and outreach related to LGBTQ youth and teachers and his support for LGBTQ communities of color in school and community settings.

“Issues of equity, diversity, and social justice will always be close to my heart, whether it’s related to LGBTQ, ethnicity, race, gender, social class,” says Mayo. “Equity is important to me.”

College in the family

That brings Mayo back to the books in his office. His great-grandfather—Charles Franklin Simpson, owner of the books—was the son of a slave: “Alfred X,” says Mayo. “We never knew his last name.”

In the 1880s, Charles studied at Wilberforce University in Ohio, joined the faculty, and later moved to Lawrenceville, Virginia, where he taught at St. Paul College. His field was social studies.

Simpson family members continued going to college. One became a professor at a state university of New York. Mayo’s grandmother’s story about integrating the schools in his hometown is so notable that he devoted a master’s thesis to her work.

“My grandma taught for 41 years, starting out in a one-room schoolhouse in Powhatan County, Virginia,” Mayo says. “She was the first African American to integrate our school system in Powhatan County in 1967.”

Mayo opens the old brown textbook owned by his great-grandfather and points to a yellowed slip of paper.

“This is the best part,” he beams. “Here is a tardy slip excusing a student for being late in 1908. It is signed by Professor Simpson.”

Read more about J. B. Mayo and the Department of Curriculum and Instruction.

Story by Michael Moore | Photo by Greg Helgeson | July 2013/updated November 2017

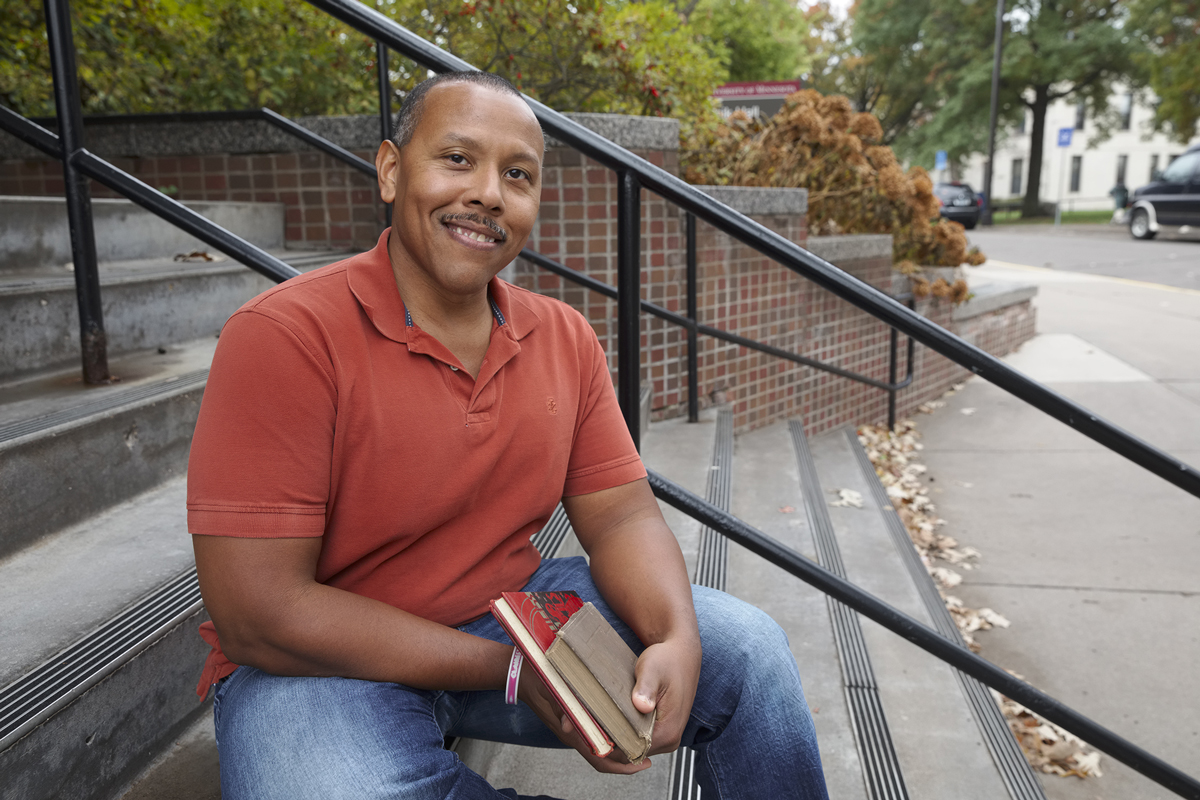

Professor J.B. Mayo Jr. with his great-grandfather’s books

Professor J.B. Mayo Jr. with his great-grandfather’s books