Jeannette Piccard, PhD ’42, gained fame twice in her life: in 1934 when she became the first woman to reach the stratosphere, and again in 1974 when she became the first woman ordained as a priest in the Episcopal church.

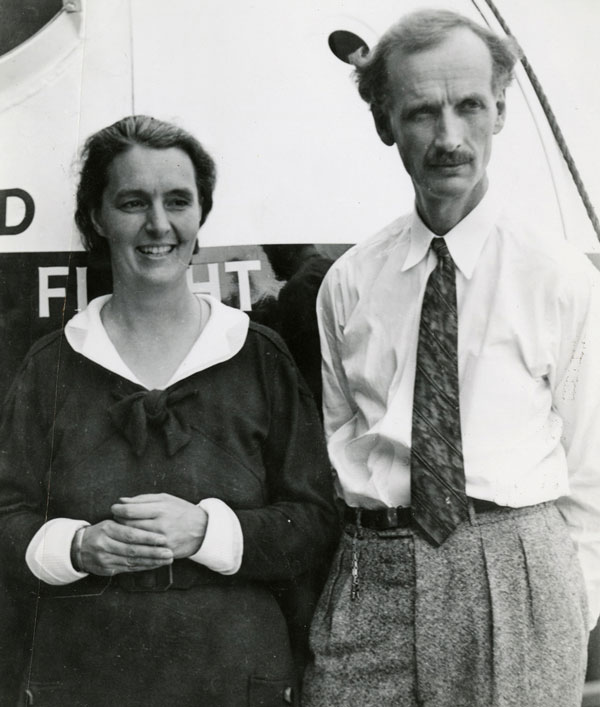

In the Discovery Gallery on the University Scholars Walk, it’s her 11-mile ascent that’s celebrated. She made it as the pilot of a seven-foot-diameter pressurized gondola carrying scientific instruments, her children’s pet turtle, and her husband, Jean Piccard—work that laid the groundwork for human space flight. When Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry named The Next Generation captain Jean-Luc Picard, it was a nod to Jean Piccard but can be considered a nod to Jeannette, too.

“I didn’t go up with him, he went up with me,” Jeannette quipped in an interview years later. Her husband needed a pilot, and she became one.

Jeannette and Jean were partners in science, invention, and engineering. When Jean was hired at the University in 1936 to teach aeronautical engineering, the dean made clear that Jeannette was part of the deal. Bob Gilruth, ’36, the Iron Range native who went on to head the NASA Manned Spaceflight Center in the 1960s, was a graduate student then and remembered her in the classroom with her husband. After Jean’s death in 1963, Gilruth hired Jeannette as a consultant for NASA during the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions.

“She was very bright, had her own doctor’s degree, and was at least half the brains of that family, technical as well as otherwise,” said Gilruth. “She was something. She was good.”

In fact, it was between her two periods of fame that Jeannette Piccard got that doctoral degree in education. And her dissertation wasn’t about either science or religion, but housing—specifically, housing for married graduate students at the U.

Her marks in all areas were connected by her powerful intelligence and spiritual life. Piccard was driven by a calling that guided her discovery.

An early vision

Jeannette Ridlon was only 11 when she expressed her desire to be a priest to her mother, who was shocked. It was 1906, and her family was Episcopalian but not particularly religious. Jeannette voluntarily attended confirmation classes the next year, took her first communion, and established a daily spiritual practice that would last her lifetime.

Born in 1895, Jeannette was one of nine children of a Chicago surgeon. She lost her identical twin sister at the age of three as the result of a fire started by a dollhouse stove, and her next-closest sister two years later to appendicitis. As she grew up, she learned to keep her aspirations to herself, but she finished high school and insisted on college, where she studied philosophy and psychology.

Then World War I intervened. At the University of Chicago, Jeannette chose a master’s degree in organic chemistry to “free a man for the front,” as the saying went. That was how she met visiting professor Jean Piccard, a Swiss pioneer in balloon technology already well known, along with his own twin brother, Auguste, in Europe. She finished her degree and they married in 1919, moving to Switzerland, where three sons were born. The youngest was an infant when they moved back to the United States in 1926 after Jean accepted a professorship at MIT, followed by a series of industry jobs.

Serenity and fun

“Who is that woman with the serene face and six horrible children?” someone was heard to inquire in a church where she attended as a newcomer. It was a story that was passed down through the family with laughter, because Jeannette did possess a remarkable sense of calm and joy, and she also was known for taking in foster children in addition to her own three boys. Robert Gilruth, for example, thought the Piccards had 12.

It was serenity that Jeannette described as the peak of her stratospheric experiences in open-air as well as pressurized gondolas. She was the first woman officially licensed to pilot balloons, an assignment she seized and completed in the summer of 1934 as she and Jean prepared for their flight of scientific discovery using a balloon leftover from the Chicago Exposition the year before.

“You go where the wind goes,” she said. “You feel like part of the air. You almost feel like part of eternity, and you just float along.”

Yet it wasn’t passive. Flying a balloon is “more fun than a goat,” she later told a Minnesota reporter. “In a balloon, I lose all sense of earthly necessity.”

That was another characteristic of Jeannette, remembered well by her son, Don Piccard, now of Columbia Heights, who grew up to become a balloonist himself.

“As a mother, she was fun,” says Don. “She liked to play, and she had a good time.” She won a limerick contest on the radio, liked to chop wood in the back yard, and always had projects going.

When their parents launched the famous flight in 1934, the Piccard boys stayed on the ground in Dearborn, Michigan, and weren’t surprised to hear their mother had brought down the gondola safely in Ohio, 600 miles away.

“No, I wasn’t afraid,” says Don, who was eight at the time.

Soon Jean was a professor in Minnesota, and the family settled a mile down the Mississippi from his campus lab.

A PhD of her own

In the late 1930s, Jeannette Piccard was in her early 40s. The first of her sons had started at the University and her youngest, Don, had reached his teens. It was time to prepare for the next chapter.

Jeannette knew college students. As she told an interviewer years later, she decided to prepare for a position like dean of women, counseling college women thinking about their future lives, and she enrolled in a doctoral program in education. When it came time to choose her dissertation topic, she said she would have preferred a topic like changing religious attitudes. Instead, she agreed to research the University’s insufficient housing for married graduate students to complement a study of undergraduate housing going on at the time. Her adviser was Mervin Neale, but it was a topic suggested by her sociology professor, F. Stuart Chapin, a leader in the application of statistics in the field.

In typical fashion, Jeannette threw herself into the task. A total of 1,745 students were registered in graduate courses, but the vast majority were part-time. A few hundred were unmarried. Armed with tape measure and meticulously designed surveys, in fall quarter 1939 she visited and interviewed in person the nearly 300 graduate students enrolled full-time or working on their theses, or their spouses, for 45–60 minutes. Toddlers often climbed onto her lap and older children played with her. The hand that had tabulated flight data recorded numbers of rooms and their sizes, numbers of windows, wattage and type of study lamps, types of heaters and kitchen stoves. For the next two years she tabulated and analyzed her data.

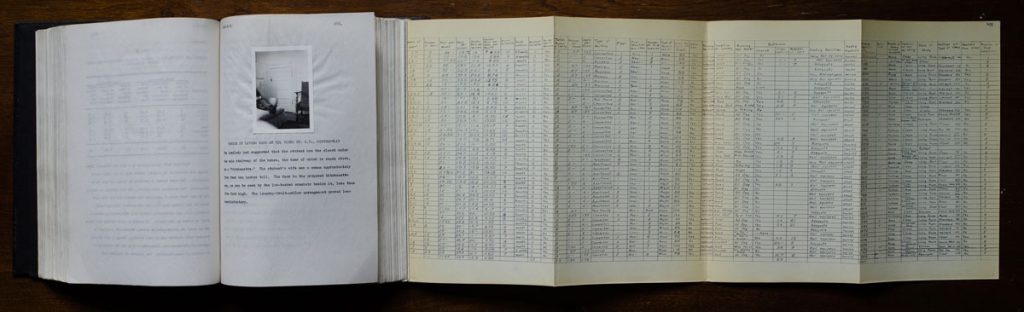

In March 1942, she defended her thesis, all 437 pages, including 111 tables, five figures, and three captioned photos of addresses with hazardous and inhumane conditions. Six pages were fold-out ledger sheets with 42 columns of data, tabulated in her neat scientist’s hand, from address and degree program to annual income, numbers of children, and fire hazards. The crowded, dirty, and dangerous conditions she found sobered her readers, even considering the Depression period. Her study became part of a growing body of data that would help to improve living conditions for married graduate students at major universities across the country.

Yet, by the time she finished, the country was again at war. Instead of looking for a job at a college or university, Jeannette applied her expertise at the local board of civil defense, working on housing for military families. She volunteered on blood drives with the Salvation Army.

Four stars shone in the window at 1445 East River Road for her naturalized-citizen husband and their sons in the service. Upon hearing the name Piccard, U.S. naval officers assigned Don to a unit using balloons to train blimp pilots how to fly without power.

And as Jeannette observed, lives were being saved by frost-free windshields on bombers, a direct result of the Piccards’ work to make frost-free windows in their stratospheric cabin.

After the war, family housing at the U consisted of trailers and Quonset huts, many built for veterans returning to school. It wouldn’t be until the late 1960s that family housing, called Commonwealth Terrace, was built on the St. Paul campus, followed by the Como Student Community in 1975.

From housing to Houston

In the post-war years, the Piccard sons finished college and started families and careers—a mechanical engineer in an industrial laboratory, a professor of political science, and an innovator in patents and aeronautics. Jean suffered a stroke in the early 1950s and died in 1963. That was also the year Soviet Valentina Tareshkova officially became the first woman in space, 29 years after Jeannette and many miles higher.

It was on a visit to speak in Minneapolis that one-time grad student Robert Gilruth, by then at NASA, saw Jeannette in the audience and recruited her to Houston.

In her new job as a consultant for NASA, Jeanette traveled around the country, speaking to students and community groups about the space program with energy, passion, and humor. After the first spacewalk by astronaut Ed White in June 1965, she often concluded her presentations with a film of that walk that continued to thrill her. She even ventured to share ideas with Gilruth and saw a few applied, such as the design of a periscope for the man-to-the-moon Apollo spacecraft.

In 1968, she received an Outstanding Alumni Award from the University, and in 1969 she spoke to high school students at Northrop Auditorium just weeks before Neil Armstrong walked on the moon in July.

In 1970, her post with NASA ended and she was back in Minnesota, where in 1971 she was ordained as a deacon in the Episcopal Church. Her final adventure had begun.

A spirit to serve

The first person to affirm Jeannette’s calling to the priesthood was Rev. Denzil Carty at St. Phillips Episcopal Church in the 1960s. The black congregation in St. Paul had become her spiritual home.

Jeannette regularly brought home someone for dinner who needed a meal, according to her granddaughter, Jane, who lived with her grandmother for a quarter while attending the U. Jeannette also found that, with age, she had acquired a gift for working with the sick and lonely elders in nursing homes. As a deacon she brought the Episcopal service and knew the comfort and connection to community it provided.

Jeannette had gained confidence and even greater skill in public speaking during her years traveling around the country for NASA. She’d also met and spoken to countless groups in the movement toward ordination for women. Now Jeannette once again took leave of her house on East River Road, this time for a year of seminary study in New York. At 77, Jeannette studied Greek and applied her incisive mind to scripture.

“None of the people who meant a great deal to Jeannette in her spiritual life had any room for women as priests—she had no support system. It shows the independence of her thinking,” says retired Rev. John Rettger, rector for an Episcopal church in Spring Lake Park at the time. “She had to make in herself, in her own mind, this tremendous leap between nineteen-hundred-and-some years of tradition and a bold thing.” He chuckles. “She was a balloonist! She had a different view.”

Rettger had never questioned the tradition. Hearing Jeannette Piccard persuaded him otherwise, and he invited her to speak at his church.

“She was thorough, almost lawyerly,” he says.

“By marshalling all this evidence, little thing after little thing, she was able to do what is the mark of true scholarship: You come up with a new way.”

Rev. John Rettger

In 1974, Jeannette was the eldest of 11 women ordinands and first to be ordained as an Episcopal priest at a service in Philadelphia, attended by her three sons and 1,500 others. The ordination, carried out by three retired bishops, was controversial and not confirmed by the church until 1976 at a convention in Minneapolis that made headlines.

Jeannette Piccard fulfilled her calling and ministered as a priest and chaplain to the isolated and homebound until her death at Masonic Memorial Hospital in Minneapolis in 1981. She lived long enough to see a granddaughter, Katherine Piccard, also ordained as an Episcopal priest. Another granddaughter, Mary Piccard Vance, became an ordained Presbyterian minister.

“She believed she could do anything,” says granddaughter Jane Piccard, ’73, “and she did.”

See a photo of Jane Piccard and her grandmother’s tribute on the Wall of Discovery in “Remembering another milestone in space.”

Read more about academic programs today that correspond to Jeannette Piccard’s work—counseling and student personnel psychology, science education, and higher education.

SELECTED REFERENCES

“The Housing of Married Graduate Students at the University of Minnesota, Fall Quarter 1939–40,” PhD thesis by Jeannette Piccard, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, March 1942.

“Mrs. Piccard rises above most women—in a balloon,” by Jacqueline Larkin, Minneapolis Star, December 7, 1955.

“In Space—Dr. Jeanette Piccard,” by Patricia Hampl, Ivory Tower, November 7, 1966, pp. 25-29.

“Dr. Piccard becomes a deacon,” caption with staff photo by Powell Krueger, Minneapolis Star, June 30, 1971.

“Forty years later, Jeanette Piccard still making history,” by Lewis Cope, Minneapolis Tribune, October 27, 1974.

Breakthrough: Women in Religion, by Betsy Covington Smith. New York: Walker and Company, 1978, with marginalia by Jeannette Piccard, courtesy of Jane Piccard.

“Rev. Jeanette Piccard dies at 86; scientist entered seminary in ’70s,” by Walter Waggoner, in The New York Times, May 19, 1981.

Robert Gilruth interview by David DeVorkin, Linda Ezell, and Martin Collins, May 14, 1986. https://airandspace.si.edu/research/projects/oral-histories/TRANSCPT/GILRUTH2.HTM , accessed May 31, 2019.

“Balloon research at Minnesota,” by Ginny Olson, in AEM [Aeronautics and Mechanical Engineering] Newsletter, University of Minnesota, ca. 2000.

“Scientific ballooning,” in Living With a Star, University of California Berkeley, 2002.

“From an Aristocrat to a Democrat: the Story of Dr. Jeannette Piccard—Recollections from her son Paul Piccard,” presentation June 11, 2004, Tallahassee, Florida, recorded with an introduction and conclusion by Jane Piccard, 2018.

Story by Gayla Marty | Photos courtesy of Jane Piccard except as indicated | Fall 2019

Jean and Jeannette Piccard emerged from the pressurized gondola after their flight in 1934.

Jean and Jeannette Piccard emerged from the pressurized gondola after their flight in 1934.