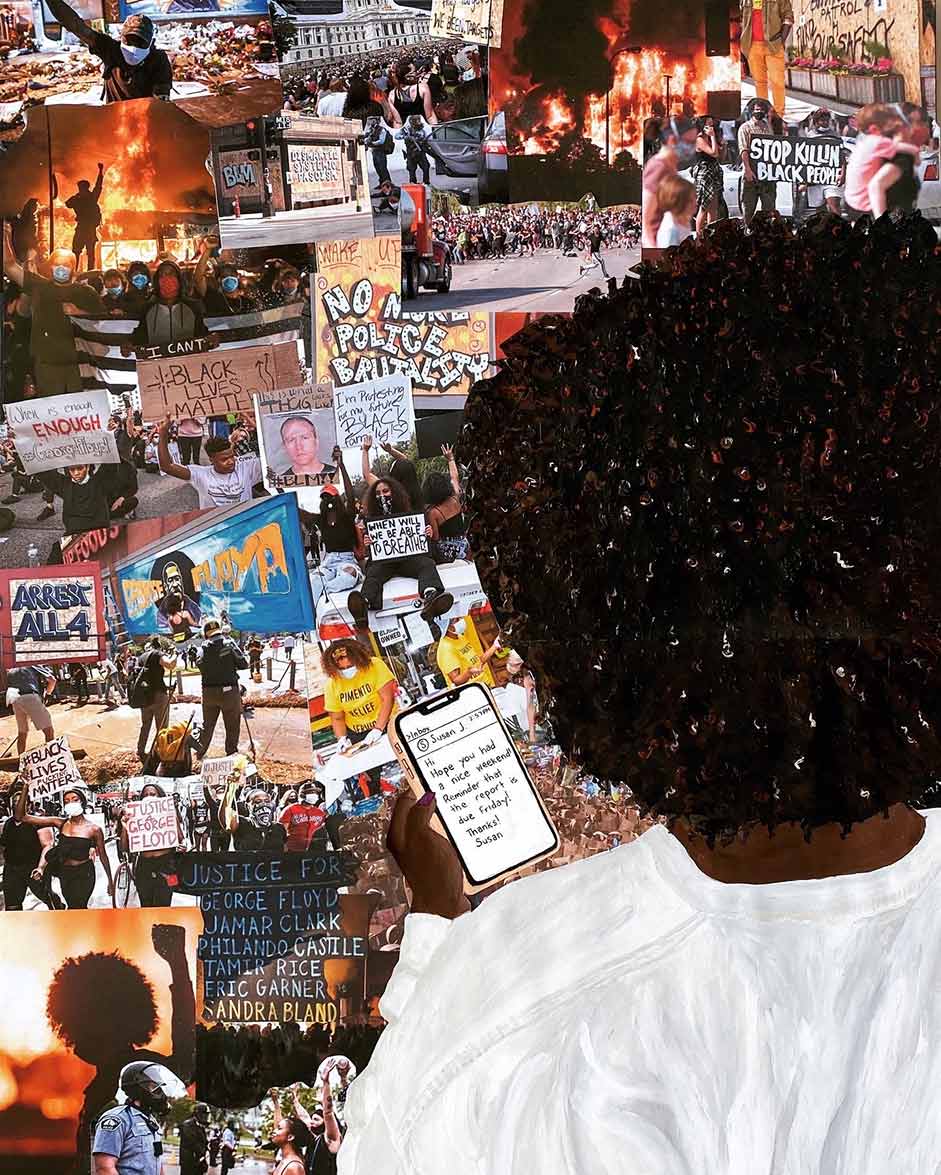

This collection of stories and commentaries contains reflections and reactions offered in the wake of the killing of St. Louis Park resident George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Generated by CEHD alumni, students, faculty, and staff, the contributions explore themes of lived experiences, resilience, caring for our community, and commitment and action pulled from a special issue of Connect magazine dedicated to all the victims and survivors of systemic racism and police brutality—those whose names are known and those whose names are unknown.

A routine day

Anonymous

At the core of racism is the assumption that a “lesser” person is lacking in comparison with a “superior” person. In academia, this translates into an assumption that the lesser person is deficient with regard to scholarship, teaching, or service.

I am not questioning the existence of variation in quality or merit. I have served on three editorial boards of prestigious scholarly journals. I have refereed over 100 manuscripts. I regularly apply judgments regarding merit.

My observation, however, is that standards vary. I see this whenever a journal editor sends blinded copies of all manuscript reviews, plus his/her decision letter, to the referees who wrote the reviews as well as to the author of a manuscript submission. This practice promotes transparency in the editorial review process. It also reveals variation in the standards applied by referees and journal editors. In numerous cases, I observe that my standards are higher than the standards applied by other referees, or the standard applied by an editor who accepts, for publication, a manuscript that I have critiqued.

When I compare the syllabus for a course that I have designed with a syllabus created by a different instructor for a similar course, I can see differences in the topics that are covered, the nature of the assignments, and the intended outcomes.

When I review curricula vitae for other faculty members, I see what they are counting as “service.” I can compare these contributions to the types of service that I have contributed.

There are clear differences in values, priorities, and standards with regard to “what counts” as excellence in scholarship, teaching, and service.

I observe that my values, priorities, and standards are well-aligned with the University of Minnesota’s mission statement—“To extend, apply, and exchange knowledge between the University and society by applying scholarly expertise to community problems”—as well as the University’s directive to engage with society’s “Grand Challenges.” I observe that the work of other faculty is less-aligned with the University’s mission statement and directive to engage with society’s Grand Challenges. In some cases, I struggle to understand the relevance and significance of the work that other faculty members produce.

My experience as a person of Color, however, is that certain members of the dominant culture make the assumption that their contributions are more significant than mine. They apply their own values, priorities, and standards and arrive at the conclusion that they are more deserving of esteem and respect. They feel entitled to act disrespectfully, to deliver barbed comments about the quality of my contributions, and to make and share false statements about me.

Within their culture, this type of behavior appears to be accepted. Positions of authority, and advancement within the profession, are controlled by individuals who share their values, priorities, standards, and judgments. Racism, and racist acts, pass unnoticed because members of the dominant culture do not see these acts as racist. Instead, they see their actions as perfectly justified, normal, routine responses to the failure of lesser persons to adhere to community standards and expectations. Much as Derek Chauvin saw himself as just another police officer responding to a routine call, in a routine way, on a routine day.

Through what lenses are you seeing racism?

Laura Miranda Bottenfield, ’17 MEd

In the face of so much hurt, pain, and injustice, I have been searching internally for what to say, what to do, how to make a difference, and how to “be the change.” We are faced with two pandemics: COVID-19 and racism. I am hopeful that a vaccine will be developed and COVID-19 will be eradicated, becoming a thing of the past. Eradicating racism however, a pandemic that has been in the U.S. for over 400 years, will take more than a quick shot in the arm.

I am a Latina woman, with the ancestry of slavery running in my veins, like most Latin American people. While I feel that the challenges for growth opportunities in corporate America are similar between Blacks and women, especially non-White women, I am still considered “White” and as such have many privileges.

Eradicating racism however, a pandemic that has been in the U.S. for over 400 years, will take more than a quick shot in the arm.

It never occurred to me when we moved to our neighborhood to send an email to the “Neighborhood Watch” group with a picture of my son to alert the community that he was my son, that he belonged in this neighborhood, that he enjoys jogging, and in silent words be really asking my neighbors to see him for whom he really is and to not call the police on him. It never occurred to me to have a conversation with my children about being pulled over and having a gun on their heads anywhere, even in the fast-food lane at McDonalds, when they turned 16 and were overjoyed with the ability to drive. It never occurred to me to talk with my children about understanding that they could have car keys thrown at them at a valet parking when they were just trying to get to a restaurant. Or that they would be asked to clean golf clubs at a golf course while trying to play golf.

I lost my composure when hearing a friend state that if she reported every time her elementary school-age Black son experienced racism, two things would happen: 1) she would not get off the phone as bullying and racism against her son happened many times throughout the day and, 2) by calling several times and being upset about racism against her son, it would only exacerbate the situation. Eventually, it could turn against her as being just another “hysterical, loud, aggressive, without control Black woman.” I am not sure about you, but I know that I would have been the “Mama Bear” if anybody mistreated my children at school. I would demand prompt action for the issue to be corrected immediately. As a matter of fact, I founded a very successful K-12, tuition-free, liberal arts, college preparatory school just so that my children, and many other children, could receive the best education possible. Not being able to stand up for my children, not being heard, not being taken seriously, and being brushed aside as another stereotypical angry Black woman would have sent me through the roof.

In trying to make sense of all of this, I am trying to educate myself. I am listening intently, reading purposefully, and searching for knowledge that in reality has been right in the open, right in front of me, but is just now sinking in. In the last few weeks I have learned a couple things I would like to share. You may know these already and I do not mean to offend. I am being transparent and humble as I am learning. Here is what I have learned and some ways I found we could help: Bring a sense of responsibility and problem-solving spirit.

Instead, I brought guilt—thinking that expressing guilt and how bad I was feeling was helping. I quickly realized that the Black community is already in too much pain. Dealing with wounds hundreds of years old that cannot heal and have not healed. They have no energy left to deal with our White guilt. Bring a sense of responsibility and a problem-solving spirit. They need us to use our White privilege to bring about change.

Educate yourself. There are many resources available. The stories I shared above about racism are not new. Our Black brothers and sisters deal with the raw experience of systemic racism every day, everywhere: in schools, colleges, and universities; the health system; housing; policies; corporate America; and the list goes on. Andrés Tapia, a senior client partner at Korn Ferry and author of the book Auténtico: The Definitive Guide to Latino Career Success, recently wrote an article “Being a true White ally against racism.” In it, he recommends a few authors to help us with our understanding of racism, such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Michelle Alexander, James Baldwin, and Robin DiAngelo. I would add Ibram X. Kendi and his book How to Be an Antiracist to the list and there are many more. And if you have not read Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, start here.

Listen without rationalizing. What lenses are you using when you see the “modern day lynching” of George Floyd? My Black colleagues have opened my eyes to the fact that the minute most of us start hearing about the Black experience is the minute most of us start rationalizing. The ability to listen deeply, to listen for understanding without judgement or without shifting the focus on us is a leadership skill we should all strive for.

Choose a side. I choose the side of justice, the side of equity, the side of anti-racism. Not just for a few days or a couple of weeks as the pain of the vaccine shot in the arm dissipates. I am in this for the long haul. I hope you are too.

Reflecting on my race journey

Bhaskar Upadhyay, Associate Professor, Department of Curriculum and Instruction

Mr. Floyd’s murder by law enforcement in Minneapolis on top of the utter hardships brought on by COVID-19 has made me reflect on my own experiences with race. I have experienced racial discrimination in different forms, some in subtle ways and others more direct and in your face. On the matters of race, I have struggled to explain what race means to my family members in Nepal, colleagues, collaborators, and students who didn’t grow up in the U.S. or countries like the U.K. Therefore many international readers of this reflection may not consider what I am about to share here as racial discrimination and prejudice, but rather with a different label such as caste (I belong to a Brahmin caste), Indigenous, SES, ethnicity, etc. All of these various labels of discrimination are about race in a different name where the key underlying theme is “master-slave relationship,” creating a social structure of “organizing human beings based on differences” to “preserve existing power structures.” This is my experience in given contexts, times, places, and with the individuals I encountered that may or not be similar to that of others. Therefore, readers should be aware of this context. My first encounter with demeaning racial experience took place in India when a group of adults called me “Bahadur.” I was 16 years old then. One of the adults asked me if I was looking for a “dishwasher job in a restaurant.” They added something like “if you were a little older you could be hired as night-watchman for a rich family’s home…that’s what most ‘Bahadurs’ do.” I have experienced this name calling many times over whenever I have travelled there, in most cases in the Hindi-speaking regions. In a literal sense “Bahadur” means “brave,” but if an Indian calls a Nepali “Bahadur” rather than by his/her/their name or a relational title such as brother, sister, aunt, grandmother, etc., then it’s directed to impose power over that Nepali. “Bahadur” was not a compliment, but telling me, in no uncertain terms, that “you are an illiterate, poor, dumb, uneducated” individual whose personal identity can be taken away in a flash—I was not “Bhaskar,” but “Bahadur,” about whom nothing more needed to be respected and learned. This singular label is a British colonial legacy of recruiting Nepali citizens to serve in the Indian and British militaries as Gurkhas, which still continues.

My travel to the U.K. in 1994 was my next international experience with racial discrimination. I was there on a British government fellowship to learn about assessment in general but with specific focus on how the University of Cambridge Local Examination Syndicate (a non-teaching department of the University of Cambridge) developed, validated, and graded K-12 assessments. I was with a colleague of mine when a White immigration officer asked us to produce evidence that our visas were “not forged.” By the way, both of our visas had “gratis” endorsements. The immigration officer then wanted to know why my colleague’s visa number and mine were not continuous. He then asked who had the missing visa to the U.K. I bluntly responded, “Ask your embassy in Nepal.” Reflecting now, very likely not the best response to an immigration officer, but I was too upset to care about his decision after 14 hours non-stop travel. I was ready to head back home. The officer then called another White immigration officer to interview me in a separate room and added something like “I need to be extra vigilant with people like you.” By now, it’s been more than an hour since the initial meeting. I was beyond caring about learning anything at the University of Cambridge. At that moment, I felt like “I had to sell my dignity; somehow be grateful; and assume silence.” My interpretation of this incident was that accented, Brown, and poor are guilty before a crime is committed and are unwanted in White peoples’ places. I first encountered what race meant in the context of the U.S. when Mr. Amadou Diallo, a Guinea immigrant, was killed by a White New York City police officer in February 1999. I had been in the U.S. just six months for my graduate study at Teachers College, Columbia University. It shook me to the core and all the stereotypes of NYC that I had learned from Hollywood movies in Nepal became real. This incident also made me aware of my immigrant status and extreme vulnerability I carried with me. One byproduct of this experience was an impetus for my interest in equity, diversity, and social justice in science education. I was not wrong about my racial vulnerabilities when I joined my current department at the University of Minnesota in 2004. I was very aware that as a junior non-tenured faculty whose work focused on equity and diversity in science education, I had to be extra cautious about how and what I shared and said. My interactions with a number of White colleagues, then and still now, were respectful, but very guarded because I had heard statements like “being diverse gives me tenure easily,” “multicultural and diversity are wishy-washy research,” and “nobody reads diversity work.”

For me, the cautionary signs as an immigrant faculty never left and probably will never leave.

These statements were cautionary signs to me as a junior immigrant faculty of my place in the hierarchy of the academy in an R1 university and how I was supposed to play in the system. For me, the cautionary signs as an immigrant faculty never left and probably will never leave. Similarly, when I first taught a diversity equity course in science education, many White MEd students and doctoral students questioned the value of it in science, which still happens in my field. But the larger point from a number of White students was about trustworthiness of a Brown faculty talking about diversity, equity, and race in science education.

My encounters with racial discrimination are mine and the interpretations are mine. The members from a dominant community (Whites in the U.S. and/or another group in another country) have to recognize that injustices, large or small, have an intentional historical arc of harm and marginalization against a group or groups. Race is one of those intentional harms in whatever form it manifests in any context, place, and time—name calling to questioning equity and diversity work. Institutions, groups, and individuals are all a part of human history, therefore, they have a responsibility to voice their concerns and take actions for injustices and show empathy not just in words, but in healing actions toward those who suffer from any real or perceived prejudices.

Did race play a role in my departure?

Na’im Madyun, former CEHD associate dean

By the fall of 1997, I was a doctoral student in CEHD. I would become a teaching specialist in the General College while getting married, having children, and continuing my doctoral studies. In 2005, I became a professor. In 2011, I had the honor of giving the undergraduate commencement address for CEHD. A year later, I achieved tenure. On December 3, 2013, I became an associate dean of undergraduate education. On August 5, 2019, I left the University of Minnesota completely.

Out of all the theories, speculations, and other forms of sense making I heard as to why I left, the more intriguing and ironic ones elevated race.

Did race play a role in my departure? The murder of George Floyd answers the question quite easily. I didn’t realize how elegantly his murder could provide insights into the complexity of the unease around race until his murder was officially recognized as a murder. No longer did anyone need to worry about theorizing, speculating, or being insensitive when saying, “George Floyd was murdered by a police officer.” A post-mortem examination protected the articulation of that statement. Yet, many still struggled to talk through, write down, or think aloud the publicly permissible statement. Other statements became easier to elevate. His death was tragic. (…even Sophocles must weep at this particular one) His loss was indefensible. (…something bad happened and that bad thing should not have happened!!)

He didn’t deserve to die. (…even though he didn’t live a particularly clean life) This can happen anywhere. (…something other than the Twin Cities should have the main attention) We are all in shock at this moment. (….) For me, the statement of shock was the toughest to absorb. I kept wondering what will happen after we adjust to being shocked?

When I was in the first and second grades, I scored at the 99th percentile on all my standardized test scores. I remember finally sharing with my mom the frustration of not getting to 100 percent. She laughed and said, “I believe 100 percent is reserved for geniuses.” From that point on, I would introduce myself to people and say “guess what, I’m one point from a genius!” In the third grade, I moved from my neighborhood school to the district-wide elementary school. Despite stellar grades and being one point from a genius, I was placed in a lower track. I remember feeling betrayed by the many Black people who told me I was a great student and a good kid. After a few months, I was moved to the top track where my eyes were greeted by a sea of White students. I remember believing that these White students must have achieved that 100 percent. I remember feeling that I didn’t belong, but I had a responsibility to stay. It would take years to recapture the joy and confidence I had before being shocked by that tragic, indefensible, all-too-common educational experience that I didn’t deserve. I spent most of my elementary to high school years trying hard to study people and “culture” so I could avoid being shocked like that again. Who wants to absorb the shock from statements of racial pain? Who wants to know that as a graduate student a police officer questioned my friend’s motive for using an ATM in Dinkytown since his driver’s license showed St. Paul as his residence? We both were standing there, but the officer said my friend was the one that looked at him suspiciously. That look was why he got out of his patrol car. My friend couldn’t settle his body afterwards and I was relieved that I didn’t give the same look. Who wants to know that I fell asleep in my office as a professor one evening only to be awakened by three janitors who asked me to show proof of my I.D.? After I produced my license, they asked me to prove that my key still worked. My hand shook as I tried to pick out the right key on the first try.

Who wants to know that it would become exhausting processing the many different, never-ending ways that people would articulate that my blackness was an asset to leadership? Who wants to know that it became existentially confusing to observe race being used as currency in one breath and then as a tax with another breath depending on the economics of the moment?

Who wants to know that it became comically paralyzing hearing the many compliments of how beautiful my large family was when I was struggling to keep my home together? There was a self-imposed pressure of trying to prove Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrong.

Every encounter, whether necessary or not, I couldn’t avoid the private calculation of how my race played a role in the interaction.

Why did they look surprised when I made that point?

Is the condescension because of my age?

Was that a smirk before saying “Dean Madyun?”

What do you mean I’m not using all my power?

Would this trust feel different if I was not Black?

Do I have a responsibility to add my own thoughts or allow this already uncomfortable conversation to end?

Am I The Spook Who Sat by the Door, the spy who sat inside the door, or the spirit of the door?

How is this person seeing me?

The statements we do not make about race, racism, and its accompanying pains provide elegant insights into what we are ready and willing to face. Did race play a role in my departure from the University of Minnesota?

Experience with policing

We have work to do, only if we are willing

Bodunrin O. Banwo, ’20 PhD

In 2018, the University of Minnesota’s police department sent out an all-campus email and alert with a mugshot picture of a robbery suspect who turned out to be the wrong person. The mugshot was of an innocent Black man with dreads who was oddly similar to me. I remember thinking at the time that this man looking back at me from my computer screen could be my ticket to being murdered by the police. In class, I began strategizing how I was going to get off campus, to my home—and safety. I started thinking of ways to hide my hair, which direction I was going to walk, and how to respond if some well-meaning student, doing their public duty, called the police to report a Black man with dreads attempting to leave campus in a hurry. During my walk home, I began to wonder, what if in the dark and cold a well-meaning police officer rolled up on me and shot me or killed me. I raised this concern with the University’s police department the next day. I told them they put every Black man on campus in danger, and that it made people fearful of a place they were paying tuition to have access to. Interestingly, the officer told me that the description came from the victim minutes after their robbery. He said they just took photos out and asked the person to pick one. Anyone who deals with trauma can understand this practice is horrific policing, and the officer admitted as much. It is bad practice to ask someone in crisis to give accurate information about their attacker. However, what made this most egregious to me is that the University police department was practicing horrific policing at a university that researches policing. If a university can not get policing right, what hope do we have for anyone else? This seemingly uncaring action was when I began to feel unsafe being on campus, which is why I started actively avoiding the space. Indeed, when I did work with Black male students at the University, I found that the feeling of not feeling safe on campus was not unique to me; it was something each of the participants spoke about. The challenge we have in front of us is an opportunity to remake the world we are in. Anything less would be an insult to George Floyd and his dream of making change. The question we have to ask ourselves, particularly at this moment: “Is our house in order?” Are we living up to our better angels, or do we need to do deep self-reflection about our positions and our thinking? From my work with Black males at the University, we have significant work to do, and it is more profound than just diversity training or using the proper pronouns and nomenclatures. What OUR students in the streets protesting are telling us is that they are ready to take on this challenge and that 40 years of diversity talk has not worked.

The sore of racial injustice—working while Black

Deseria Galloway, ’94 MSW

George’s death highlights a larger and more devastating condition permeating throughout law enforcement.

I was a child protection investigator for almost 24 years. During the course of conducting an investigation, the person I was at the home to investigate, unbeknownst to me, called the police and reported that I was trying to break into her home and tore the screen door off its hinges.

As a result, the police came four cars deep, with guns drawn, one demanding that I put my hands on the steering wheel, while the other officer was demanding my I.D. I was completely confused and caught off guard, shaking in my boots. I heard one officer on radio said we have one Black female suspect in the car and in search of the second suspect (which they never located). I was so messed up, I found two I.D.s: one was my University of MN I.D. and the other was my driver’s license and business card. I threw them out of the crack of the window while the officer kept using his baton to hit my windshield as he was yelling at me. He never really permitted me to speak. It was not until one of the officers (female) said, “Something is not right here. I do not believe that this was a burglary in progress.” Only after 25 minutes did the officers put the guns back into their holsters. They started leaving one by one, but the officer who kept hitting my windshield with the baton pulled his car around and parked in front of me and sat there an additional 15 minutes after he told me I was free to go. He never gave an apology or anything. I was so messed up crying. I returned back to the client’s door and she answered and said, “Oh, I thought you were going to hurt me.” My reply to the client was “Let’s just get through this investigation.” The next day, I reported the incident to my supervisor. Nothing ever happened as a result. I did nothing wrong “working while Black,” but I was treated like a criminal and demeaned by both the client (White woman) and six officers (all of whom were White). There is nothing worse than being viewed as a threat just because of the color of your skin. The officers were successful at demeaning and devaluing who I was as a human being.

Flashback to ’64

David Nathanson, ’73 PhD

I was registering voters in the South in the early 1960s. In a mixture of youthful curiosity and absolute stupidity, I attended a KKK rally advertised as “open to the White public” in South Boston, Virginia. Marshall Kornegay, the Grand Wizard of the KKK, said to me, “Where you from, boy?” when he heard my New York accent. Confederate flags were shoved in front of my face. Angry looking security, wearing fatigues and what looked like World War II army helmets, approached my friend Rick and me. I heard Kornegay’s voice in the background say, “Get them off the field.” I was sure it was 1864. Rick and I ran toward my car, a 1964 Oldsmobile. No, I wasn’t a time traveler.

When I saw the murder of George Floyd on TV, I thought of the KKK rally 56 years ago. The more things change, the more they stay the same. A not-so-obvious characteristic, my accent, almost got me killed. What must it be like for people who have something as obvious as a different skin color? Walking, driving, jogging while Black means, I assume, always looking over your shoulder, always being wary, always hoping those in power are reasonable people. I try to be optimistic, but then I see what happened to George Floyd, and the unyielding 40 percent who support Trump, and I’m saddened. All we can do is keep fighting and try to elect leaders who are decent human beings. The police killing Floyd was the trigger, but the general atmosphere of distrust, selfishness, and ignorance was the ammunition.

Why I am a cynic

Donald Welch, ’62 General Education

After I graduated from the U of MN in the winter quarter of 1965, I began a Peace Corps 10-week training program at Springfield College in Springfield, Massachusetts. While I was nearing the end of my training program, one night I witnessed the tail-end of a police action taking place. It was a raid on a bar in a Black neighborhood in Springfield. When I asked some Black individuals in the area what was happening, I got a cool reaction, and even non-responses. Apparently I was seen as the enemy since my skin is white. Then all of a sudden, all hell broke loose.

A policeman approached a parked car filled with Black individuals. He opened the back door of a vehicle and started to pull out a male occupant from the backseat. When he got the man out he started beating him with his police baton. He was joined by several other police officers, and they proceeded to drive the man toward a paddy wagon parked nearby as they beat the man unmercifully. Once in the paddy wagon, several officers jumped inside and continually beat the man with their clubs. At no time was the victim resisting arrest. He only raised his arms to protect his head. The police were so intent with their beating that they did not pay any attention to me nearby, an eyewitness. I was in shock. When I retreated from the beating scene, another officer ran over to another car that was occupied by one Black man. The officer pulled him out of the car and hit him with a blow to the top of his head, splitting his head wide open. What I witnessed was blatant police brutality. Although I was scared to get involved, I agreed to do so because of my conscience after seeing such an injustice. I was young and naive. I thought such type of police behavior only happened in the Southern states that were actively fighting against racial integration at the time. These victims of the police beatings were charged with resisting arrest. When I came to court to testify, I was brought into the district attorney’s office. He tried to persuade me not to testify on behalf of the defendants, even insinuating it was not in my future best interest to do so. Under oath, I testified in court that the accused were not resisting arrest, and the situation was more on the order of a police riot. Despite my testimony, the defendants were found guilty of resisting arrest. It was a kangaroo court. They disregarded my testimony. That was over 50 years ago. Nothing much has changed in those 50-plus years. As an older man I have become more cynical. Once this latest commotion over police brutality and the killing of George Floyd blows over, the bad actors in the police departments will still be around. Not much, if anything, will change. As long as the police unions defend these criminals wearing police badges, the beatings and killings will continue. Since the killing of George Floyd was recorded on a cell phone, perhaps this time the officer will be convicted and sentenced to prison for a while. While I believe the vast majority of the police are good and law-abiding, none of them are willing to blow the whistle on fellow bad cops. This fact, plus police unions defending the guilty, will assure no real change will occur in the near future. Racism is systemic in our society.

Toward a radical Black humanity

Chelda Smith, ’14 PhD

There aren’t two sides to this. Black Lives Mattering is the only “side.” That a debate even exists about the issue of Black lives having value is hurtful, dangerous, and damaging. It’s dehumanizing. This note is written to speak to those that agree that Black Lives Matter more than it is intended to convince those who disagree. At this time, I am not willing to debate or argue my humanity to anyone, anymore. It is too costly and futile—for me.

Instead, my purpose is to unpack whose Black life matters because I realize for most, Black lives or the Black community is synonymous with Black cisgender heterosexual men. This narrow appreciation of the terms is common among both non-Black folks and Black people. So, this note is intended for those who concur that Black Lives Matter but have not radically interrogated the complexity of which Black lives have been centered, amplified, and for whom justice has been sought.

In Titus Kaphar’s June 15, 2020, Time magazine cover, he paints a portrait depicting the fear Black mothers feel for their children’s lives. I have questions: Who is protecting the mother? Does it matter if the child is undocumented or has a disability? Does it matter if the child is Trans?

The traditional red border on the Time magazine cover featured the names of 35 Black men and women who’ve been murdered. Notably, the names of Black Trans folk murdered by police weren’t included. Why not? Although Tony McDade was killed by police just days after George Floyd, the absence of his name passively justifies his death.

#BlackLivesMatter may have been a sufficient reignition to the racial justice conversation in 2013, but in 2020 and the advent of #SayHerName we must demand that #AllBlackLivesMatter. #All, here, is about intersectionality. The qualifiers matter because the term Black does not sufficiently account for the lives of those who are multiply marginalized. This includes Weird, Queer, Trans, Hood, Incarcerated, Homeless, Undocumented, Nerdy, Fat, Dark Skin, Unemployed, Substance-Addicted, Paroled, Disabled, Underemployed, Loud, Problematic, High School Dropout, Muslim, Single-Parenting Black Lives. All Black Lives. Every Black person.

My intent isn’t to disparage Kaphar or his work. Rather, I invite you to consider how much we, the public, seek to streamline a complex and systemic issue into a neat narrative with ideal victims. It’s dehumanizing to limit the face of any systemic problem to just one faction. The convenience inherent in that rationalizing is akin to the practice of tokenizing outlying Black voices to affirm one’s bigotry. Like those who look to Candace Owens and Ben Carson as the authority on Black experiences while ignoring the millions of Black people stating counternarratives, the engagement is disingenuous and marginalizing if #BlackLivesMatter doesn’t intentionally include ALL Black lives.

Black women EXIST and their oppression in the United States has been alongside Black men since 1619. There isn’t a time in American history when Black women had the same privilege of protection as their counterparts. Black women, too, are murdered by police. Black girls are adultified by teachers and sexualized by adults. Black women’s pains are disregarded by medical professionals, and their beauty is disqualified by artists. Black women are marginalized by White feminists and used by White liberals. Systemically. Black women are humans, too, and their lives matter.

I see the injustice to humanity and hear the words from the reverend echo in my ears, “Get your knee off our necks!”

-David Stahlmann, ’87 Elementary education

These atrocities and so many others could be said of any Black person, but they are magnified when Black people exist at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities. How do mental health professionals respond to Queer Black girls? How do educators provide equitable learning experiences for Trans and low-income Black youth? How are administrators humanizing Black immigrants with disabilities? Even in victimhood, Black people are not a monolith. Black children, women, Christians, Muslims, immigrants, and a countless list of other social locations are experiencing anti-Blackness and the violence inherent in it. The murders are the zenith of White supremacy and terrorism. However, everywhere and daily—in hospitals, at work, in schools, in the streets, in the media—Black folks are subject to micro anti-Blackness and dehumanization.

As humans, Black people are entitled to the full range of human emotion, experience, and expression available in the world. There is no quality, characteristic, behavior, or status that a person or community can take up that could delegitimize their humanity. If police could humanize Dylann Roof during his arrest enough to buy him Burger King when he was hungry, then why do any Black people have to die in police interaction and custody? Police saw the humanity in Roof’s hunger after he killed nine Black Christians in their house of worship, but they couldn’t humanize George Floyd or Eric Garner as they cried “I can’t breathe.” Again, why do any Black people have to die in police interaction and custody?

I’m tired. I said I wouldn’t debate or argue my humanity to anyone anymore and yet I did. At the time of this submission, the police officers who killed Breonna Taylor, a Black woman, on March 13, 2020, have yet to be held accountable. Not a single officer announced themselves before ramming down her door and firing 22 shots, shooting Breonna Taylor eight times, killing her. Where’s the humanity? The justice? I’m tired.

#BlackLivesMatter

Changes are needed all the way from the top

David Peterson, ’67 BS

In my lifetime I witnessed many inequities and tragic events. However, what I saw in the death of George Floyd was perhaps the most upsetting occurrence. The protestations that followed—especially the overwhelming response seen in my home state of Minnesota—have reassured and restored my belief in humanity. We need to resolve these issues on every level, starting with the executive branch of the United States.

The revolution begins in the classroom

Patricia Rufino, Professor, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, CEHD Visiting Scholar

I am a Brazilian Black woman, mother of two Black boys, wife of a Black policeman, a former school teacher, and now university professor and academic director. I am the product of a land invaded by White settlers, which took our life and dignity. The fruit of Paulo Freire’s teachings, which influence my political thought and activism. A descendant of kings, queens, warriors, and workers who came to Brazil enslaved. A survivor of a suffocating White supremacist school system. I am part of less than one percent of Black university professors in my country. How can I possibly express in a short paragraph a lifetime of pain and struggle?

We must realize and reflect upon the fact that racism is not an isolated problem to be solved in a laboratory, but it is our lived experiences that we are charged with understanding. The time is now to return to the political antiracist agenda of education. Whether in Brazil or the United States, the revolution begins inside the classroom.

The peoples’ sentiment vs. media

Steven Pliam, Department of Family Social Science

I have noticed a disconnect between how the government and media continue to portray what’s happening compared to the actual pulse of the people. For example, you constantly hear the media express the sentiment that “The death of George Floyd was terrible but the destruction of property has to stop!” Whereas I believe that most of us who protest what we’ve seen align more with the reverse sentiment that “The destruction of property was terrible but the brutal police killing of Black people has to stop!”

Discovering a new power

Christina Woods, ’91 BS, ’95 MEd

It was three days into the protests and riots when I finally felt the deep trauma I’ve packed away from my life. That moment “of feeling” tore me apart in ways I thought I’d never be able to put back together. Memories suppressed from my childhood and young adult life came ripping through my body, leaving me shaking, confused, exhausted, and fearful.

After realizing this and admitting to the pain I live with due to it—I started taking advantage of a new-found power—I realized that I have a platform to share and speak about this.

The Minneapolis protest and riot has broken open a thick vessel keeping the construct of race hidden from view. I feel it. I still shake, feel confused, exhausted, and fearful. But now, with the help of seeing so much, hearing so much, and verbalizing so much about the reality of racism, White privilege, apathy, and more—I’m feeling better, stronger, credible.

Mr. Floyd’s last words

Please, man. One of you listen to me.

I can’t.

Forgery for what?

For what? Please, man. I can’t fucking breathe.

Thank you. Thank you.

Ow, my wrists, sir.

Please.

I can’t breathe.

I can’t breathe.

I can’t breathe.

Momma. Momma.

Momma. Momma.

Momma.

Momma. Momma.

Alright. Alright.

Oh my God. I can’t believe this.

I can’t believe this.

I can’t believe this.

I can’t believe this.

I can’t believe this, man.

Momma, I love you.

Tell my kids I love them.

I’m dead.

Can’t breathe for nothing, man, this cold blooded man.

Momma, I love you.

I can’t do nothing.

My face is gone.

Can’t breathe, man.

Please. Please let me stand.

Please, man. I can’t breathe.

My face skinned up bad.

My God.

God.

I’m dead.

Look at my face, man.

Please. Please.

Please, I can’t breathe. Please, man. Please.

Please man, somebody help me.

I can’t breathe.

I can’t breathe.

I can’t breathe.

Can’t breathe.

My father just died this way.

Man, I can’t breathe. My face, it’s skinned up. Man.

I can’t breathe. Please, your knee on my neck. I can’t breathe, shit.

I will.

I can’t move.

Momma.

I can’t.

My knee. My neck.

Through.

I’m claustrophobic.

My stomach hurts.

My neck hurts.

Everything hurt.

I need some water or something. Please. Please. I can’t breathe, officer.

They going to kill me. They’re going to kill me, man.

Come on, man.

I cannot breathe.

I cannot breathe.

They’re going to kill me. They’re going to kill me. I can’t breathe.

I can’t breathe.

Please, sir. Please.

Please.

Last Words

Ebony Adedayo, PhD Student, Department of Curriculum and Instruction

Read through this carefully. And as you do, if you are familiar with them, also recall Jesus’ last words on the cross as he was also being lynched. Like James Cone said, among so many others, we must recognize the connection between the crucifixion of Jesus by the Roman government and the lynching of Blacks by Whites in the United States. To not see the connection is to persist in blindness and willful ignorance. We are WAY past the time where those who profess to be believers can say that they love this Jesus and cannot love Black lives. But don’t just love us when we become a popularized hashtag because of state-sanctioned violence. Love is trendy then. Love us now. Love all of us. Queer. Straight. Christian. Muslim. Agnostic. Buddhist. Male. Female. Trans/GNC. Temporarily able bodied. Single. Married. Parent. Childless. College educated. High school drop out. Hood. Bougie. Clergy. Janitor. Essential worker. Administrative assistant. Young. Seasoned. Whether our hair is straight. Kinky. Locked. Or shaved. Wherever we show up. However we show up. Especially when we are calling you out, in, or up because of racist BS and challenging you on your anti-Blackness. Love us beyond weak a$$ platitudes, prayers, and well wishes. Beyond tokenized attempts at representation. Beyond symbolic displays toward racial equity. Beyond empty rhetoric and half-baked promises. Beyond media attention. Beyond secret DMs where you confess your love for us while no one is watching, still failing to hold others around you accountable. Let love be action oriented. Let love be the highest expression of your love and concern for all Black lives. And let it be so today, right now, so that we do not tomorrow find ourselves recounting the very last words of Black people gone too soon because the world failed to affirm our worth and failed to honor our breath.

Guest Editors:

Saida Abdi | Assistant Professor, School of Social Work

Nina Asher | Professor, Department of Curriculum and Instruction

Stefanie L. Marshall | Assistant Professor, Department of Curriculum and Instruction

Tania D. Mitchell | Associate Professor, Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy, and Development

Top Splash Image: Asha Omar, Photo 1: Mani Vang, Photo 2: Corpus Delicti from the Noun Project, Photo 3: Asha Omar, Photo 4: Pexels.com by Retha Ferguson, Photo 5: Kirsten Mortensen

Photo 1

Photo 1