IMAGINE A GROUP OF BLACK STUDENTS born into a newly and reluctantly desegregated South. Their K–12 education is experienced during the implementation of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, the passing of Title IX in 1972, and the publication of “A Nation at Risk” in 1983. Achievement, opportunity, and relationship gaps are decades away from being present in their everyday language but are very present in explaining their everyday observations of persistent inequality.

These students have a passion for addressing inequality in their local schools and surrounding neighborhoods. They attend Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) to focus those passions and their careers. In college, they find not only validation for their personal and professional aspirations but also affirmation that their particular talents are needed to reduce persistent education gaps and contribute to effective educational strategies.

The chairs of their respective departments come to these students with an opportunity to channel their passions, address inequality, attain advanced degrees, and receive stipends while doing so. The only requirement for these black undergraduates from the South is that they go north to Minnesota and become teachers or other educational professionals.

IMAGINE A UNIVERSITY with a land-grant mission, a history of access, field-shaping educators—and a predominately white teacher education program during a time of challenging racial demographic shifts and a widening achievement gap.

Concerned educators, administrators, and community members in Minnesota commit to a plan to increase the number of black teachers as well as provide students access to the range of educational careers and degrees. Students are expected to become graduate assistants with faculty mentors, and they have opportunities to contribute to research and educational projects.

The passion is present, funding sources are available, and the need is enormous. The pieces are all in place with one exception: This University needs talented black undergraduates with a passion for being educators who are willing to entertain the possibility of making Minnesota home.

In the late 1980s, the University of Minnesota’s College of Education—now CEHD—secured funding from the Bush Foundation to partner with nine Historically Black Colleges and Universities to recruit talented undergraduates for its teacher education programs. The aim was to diversify the teaching workforce in Minnesota.

The HBCUs were selected due to their track records of training and developing black teachers. At the time, HBCUs constituted only 3 percent of all higher education institutions but enrolled 14 percent of all black students in higher education. In 1989, HBCUs conferred 32 percent of all black bachelor’s degrees—19,758 of 61,046.

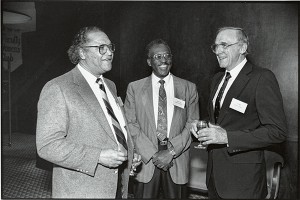

With the pioneering efforts of Josie Johnson, a senior fellow at the University and a former regent, along with then dean William Gardner and professor Jean King, the Common Ground Consortium era began.

Founded on sharing

“The idea was to share,” Johnson remembers. “Our teachers from HBCUs brought to campus techniques and methodologies for supporting black students in college classrooms. The University provided those students with research experience to make them even better educators. Urban and suburban areas got excellent black teachers.”

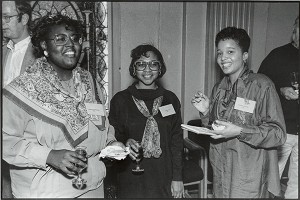

“University administrators and professors partnered and met with faculty members from HBCUs along with teachers and administrators from Minnesota K–12 schools,” according to Vanessa McKendall Stephens, the first CGC coordinator. “Together they explored the potential relationships; addressed student, faculty, and institutional expectations; and discussed how students would both contribute to and benefit from CGC, the University, schools, and community. Yearly evaluations supported learning about program effectiveness and needed adjustments. This consortium of professors, administrators, school leaders, and students met yearly to discuss progress, plan, and celebrate.”

Over the years, the consortium evolved to become a space for the development of black intellectuals in CEHD with a greater emphasis on doctoral recruitment, critical consciousness of thought, and social engagement.

From 1989 to 2015, more than 140 students participated in the consortium. They left CEHD to become teachers, guidance counselors, principals, professors, deans, educational consultants, superintendents, and in the most recent years, academic researchers and faculty members at distinguished colleges and universities, in Minnesota and elsewhere.

Creating a space

Today the CGC provides support to 10 graduate students in seven programs across five departments of the college. As each student graduates, a new student joins. Support takes the form of a graduate assistantship, a faculty mentor, professional development, and a space for shared dialogue.

The students gather every other week during the academic year to talk through the intersection of current events and historical trends, reflecting on being a black graduate student on a predominately white campus. Part of the success of CGC has come from the space the students co-create.

“I need a community of black peers to process, reflect, and understand what I am going through as a black graduate student in Minnesota,” says Karyn Cave, a master’s student in the School of Social Work.

“CGC has become a space that has offered me relief from the daily social stressors that come from being a black graduate student on a predominately white college campus,” says Justin Grinage, a doctoral student in curriculum and instruction.

These experiences are echoed by Brian Lozenksi, now an assistant professor of multicultural and urban education at Macalester College in St. Paul.

“CGC was an invaluable experience because it provided me with a space to work through ideas without having to worry about singularly representing a racial andcultural group of people,” says Lozenski. “In a predominantly white institution like the University of Minnesota, these spaces are almost nonexistent. CGC provided me with a community and colleagues who I could discuss issues with from a different perspective.”

“For me, CGC existed as a hotbed for black intellectual thought and scholarship,” remembers Chelda Smith, who was a CGC doctoral student in curriculum and instruction. “Most of all, it was a place of validation at an institution that didn’t always extend that merit to black and brown students.”

Honest, direct, and caring

A conversation between Smith and CEHD staff member Serena Wright has become a repeated CGC narrative. Wright coordinates consortium events and is a frequent presence in the CGC space, often engaging students in honest, direct, and nurturing conversations. One day Smith met Wright while walking across campus.

“What happened to your shine?” Wright asked in her typical affirming yet questioning manner.

“Huh,” Smith responded. “Nothing—I think I just had a long day.”

After returning home, Smith reflected on the exchange and realized that she wasn’t the same student who walked onto the U of M campus as a first-year graduate student. Somehow, she had lost her confidence and her “shine.” The next day she tracked down Wright and asked her for a little time to just talk in her office. That talk lasted for several hours.

“I didn’t realize I ‘lost my shine’ until you asked me that question,” Smith told Wright. “I didn’t even know I wasn’t being me. Thank you for asking me that question. Thank you for noticing. Thank you for even caring to say it out loud.”

Today Smith is an assistant professor of teaching and learning at Georgia Southern University. The beauty of what Wright offered to Smith and continues to offer in the CGC space is what the students also offer each other, during the program and for years afterward.

“The friendships I established during my four years in CGC are still friendships I cherish today,” says Smith.

Celebrating successes

I myself began my academic life as a Head Start student raised in a small Mississippi River town in Arkansas and came to Minnesota in 1997 because of the CGC. Some of my assumptions of Minnesota were proven false, and fortunately some of my assumptions about the scope of my capacity were also proven false. Today as a professor and associate dean in CEHD, I coordinate the CGC program.

Admittedly, an easy explanation for why I stayed in Minnesota was that I discovered clearer answers to the question “Who am I?” during my time in CGC. Accompanying that experience was a comforting combination of purpose, loyalty, service, and responsibility to CEHD. It would be inaccurate to say that I can’t imagine what I would be without CGC, because honestly I can—I would be an educator concerned about inequality. But I would be a concerned educator somewhere else.

I entered the program at the same time as my colleague Tabitha Grier-Reed, who is now an associate professor in CEHD. Part of her legacy is the creation and continuation of a gathering and social networking space for black undergraduates. In a 2013 article published in the Journal of Black Psychology, she described these spaces as important for providing safety, connectedness, validation, resilience, intellectual stimulation, empowerment, and a home base for black students (Grier-Reed, 2013).

Of course, our work is never done. It continues. But it is important to reflect on successes.

“I believe CGC was one of the most significant accomplishments in building academic partnerships to increase the diversity of our student body at the University of Minnesota,” says former CEHD dean and University president Robert Bruininks. “I believe this has been a highly successful graduate and leadership development program, one of the most successful in higher education.”

Dr. Josie Johnson says, “I feel proud to have been one of the designers.”

“The Common Ground Consortium program afforded me the invaluable opportunity to excel academically through a teaching [and] research assistantship and a paired faculty mentor, expand my professional development through bimonthly cohort seminars and community volunteering, and discover my scholarly identity within CEHD and society,” says Azizah Jor’dan, now a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard Medical School.

The Common Ground Consortium was created two decades before we began to publicly debate the wisdom of declaring that Black Lives Matter. It has allowed for engaging in difficult and healing discussions on mattering as a black life at the University of Minnesota and beyond.

For more than 25 years, CEHD has been home to a program that encourages black graduate students to share their research experiences, professional networks, navigational strategies, professional aspirations, career opportunities, societal fears, critical observations, and personal identity growth so they can focus their passions and push for educational experiences—from preschool to grad school—to reduce inequity and create more common ground.

Story by Na’im Madyun | Spring/summer 2016

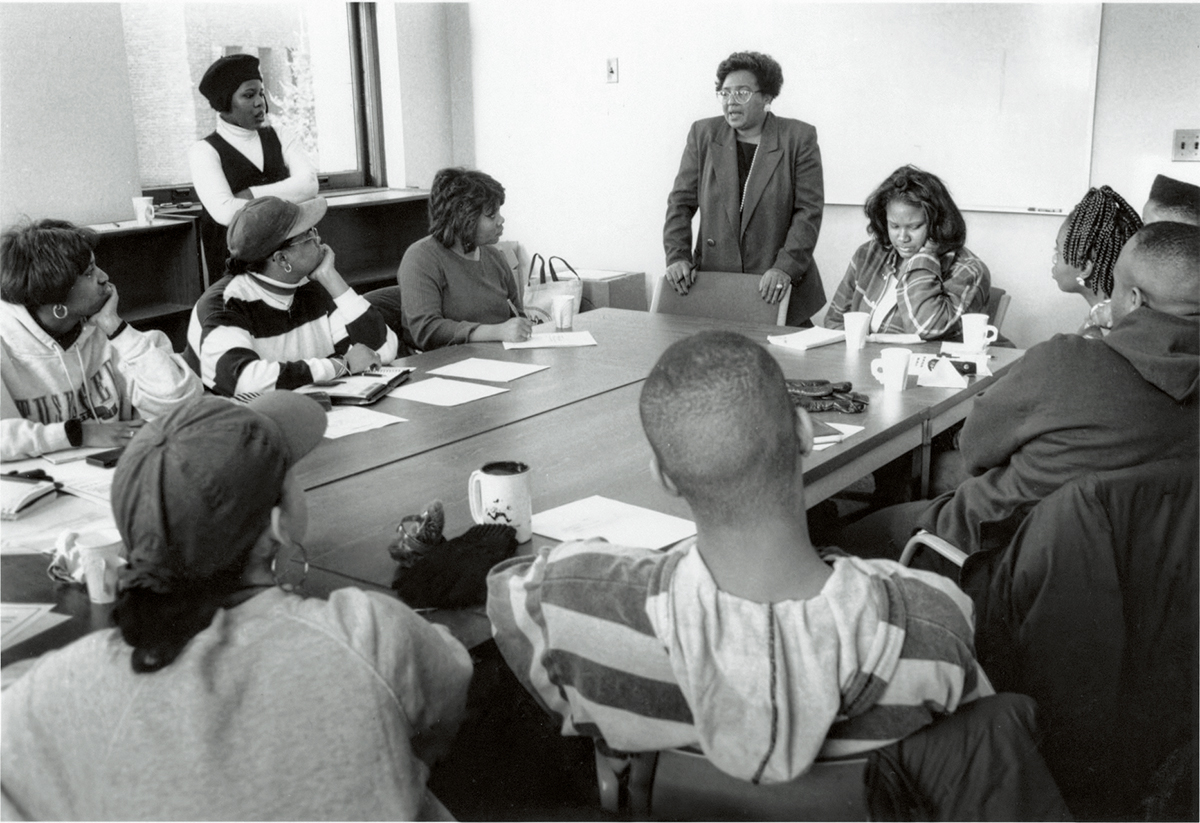

“What are you students looking for in order to stay in Minnesota after you graduate?” asked Essie Johnson, diversity coordinator for the Apple Valley/Eagan/Rosemount school district, at a 1995 meeting of the CGC. Photo by Leo Kim.

“What are you students looking for in order to stay in Minnesota after you graduate?” asked Essie Johnson, diversity coordinator for the Apple Valley/Eagan/Rosemount school district, at a 1995 meeting of the CGC. Photo by Leo Kim.