Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects more than 10 million people worldwide—1.5 million in the United States alone. There is no cure, but there are treatment options through medication and neural implants.

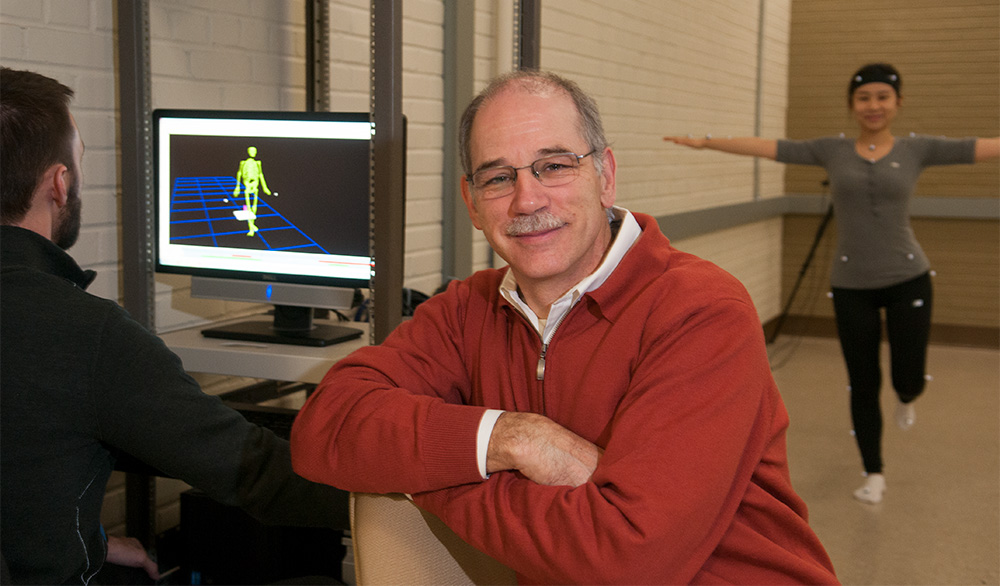

Jürgen Konczak is dedicated to discovering more. Konczak is a professor of movement science in the School of Kinesiology, where he also directs the Human Sensorimotor Control Laboratory (HSCL). One of his lab’s major initiatives is studying the link between sensory and motor systems to develop behavioral treatments for Parkinson’s disease.

“A lot of patients have reduced body perception, or proprioception—our ability to sense or feel our limbs and body movements without seeing them,” Konczak explains.

“Part of what we do in our lab is to develop behavioral therapies for learning or relearning motor function in balance and fine motor skills.”

School of Nursing researcher Corjena Cheung contacted his lab because she was interested in studying yoga as an effective behavioral therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Balance, particularly when standing and walking, can be a challenge for Parkinson’s patients, and Cheung wanted to determine whether hatha yoga, which involves body postures and breathing techniques, could have a positive effect. She was also curious about the impact of yoga on patients’ emotional well-being. Konczak and Cheung collaborated on a study to learn more.

Last fall, 20 subjects with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease participated in a 12-week program of hatha yoga. Konczak and his graduate students performed pre-tests on participants to collect baseline information on balance while standing and walking followed by post-tests after the yoga program was completed. Meanwhile, Cheung’s team performed blood draws to measure levels of cortisol, which can indicate stress and anxiety as well as well-being and happiness. The lab is now analyzing the data.

So far, analysis on data related to standing posture is positive, says Konczak. The clinical rating scales also indicated reductions in participants’ motor symptoms after they completed the yoga program. Data analysis will be complete by February.

Does Konczak see potential for yoga in treating Parkinson’s disease? More analysis and study are needed, he says.

“Many people with Parkinson’s disease are looking for ways of actively fighting it,” he says. “We are seeing more and more exercise groups for Parkinson’s patients, such as ballroom dancing or boxing, that may be helping reduce symptoms and increase well-being. Yoga may be one more way.”

Konczak would like to see more clinical trials to study the efficacy of yoga. He points to one outcome that may be more difficult to assess in a standard research study. He and Cheung met after the study to discuss the effect of the social aspect of Parkinson’s patients engaging in physical activity.

“It may not be quantifiable,” he says, “but is there value in the social contact, bringing people with similar problems together, having them feel part of a group that is working toward a common purpose?

“Yoga is about being in tune with your body—that’s the point of the practice,” he continues. “And since Parkinson’s disease requires a patient to be acutely in tune with their body, it makes sense to look at yoga as a treatment.”

An international quest

Beyond Parkinson’s disease, Konczak’s research relates to other conditions, including ataxia and dystonia. Recent projects have investigated the usefulness of robotic rehabilitation as treatment for stroke and Parkinson’s disease. One study tested whether a new tennis racket design reduces muscle fatigue and injury risk in tennis players.

Konczak’s laboratory is regularly approached by industries that seek its expertise in device and human field testing. He collaborates with engineering and clinical researchers in Germany, Italy, and Singapore.

His career path illustrates a quest to understand how the nervous system controls human movement and how disease alters brain function that leads to movement disorders.

Konczak grew up on Germany and received his B.A. in philosophy and sport science at the University of Münster. He came to the United States for graduate study—a master’s in sport science at the University of Idaho, a Ph.D. in kinesiology from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and a postdoc in psychology at Indiana University—before returning to Germany. There he pursued research in neurology at the universities of Tübingen and Düsseldorf and completed a postgraduate doctoral degree in psychology before joining the Minnesota faculty in 1999.

In addition to his faculty position in the School of Kinesiology, Konczak is an adjunct professor in neurology, holds graduate faculty appointments in cognitive and neuroscience, and directs the U-wide Center for Clinical Movement Science. He’s engaged in interdisciplinary research projects across the University, from nursing to veterinary medicine. Beyond the U, his appointments include senior researcher at the Italian Institute of Technology in Genoa.

“The brain is one of the last frontiers to human knowledge,” says Konczak. “What drives me and the research in my lab is to enhance our understanding of these disease mechanisms and to translate such knowledge into devices or interventions that may help people with neurological conditions.”

Learn more about Jürgen Konczak, the Human Sensorimotor Control Laboratory, and the School of Kinesiology.

Story by Marta Fahrenz | Photo by Dawn Villella | December 2016