News

Advancing Inclusion

ICI’s Latest Bold Steps Echo Its Roots

How many young children are diagnosed each year with autism? What’s the best way to keep students from dropping out of school? Why are direct support worker shortages at crisis levels?

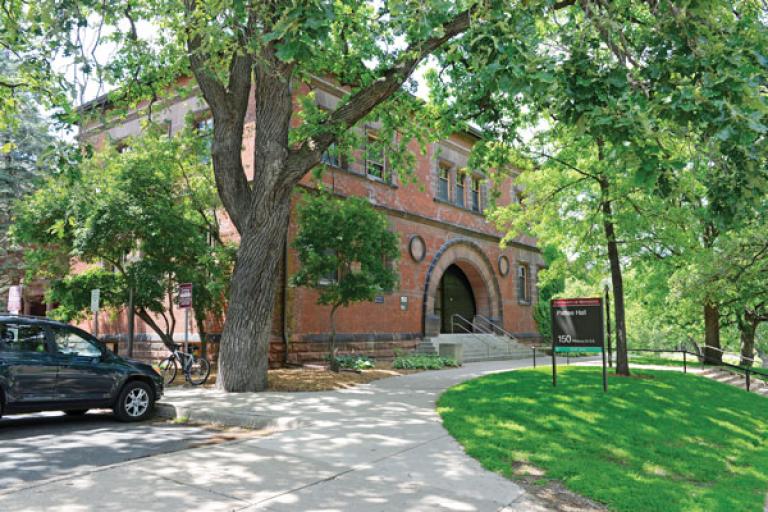

Answers to these big, timely questions and many others unfold daily in perhaps an unlikely spot: Pattee Hall, a 130-year-old sandstone edifice on the Knoll Area of the Twin Cities campus that once housed the University’s first law school.

Blending old and new is familiar ground in Pattee Hall, however, where a dizzying array of 70 active research and training projects of the Institute on Community Integration (ICI) come together to advance a shared vision: a world that fully embraces and empowers people with intellectual, developmental, and other disabilities.

Officially, ICI was founded in 1985, but its roots go deep to the civil rights era that informed the early work of former University President Robert Bruininks.

“We were trying to envision a different future, a future that really embraced the advancement of rights and inclusion of people with disabilities in society, whether they were in schools or in work or community settings,” Bruininks reminisced in an interview for ICI’s 30th anniversary in 2015. He described founding and leading ICI as the most rewarding work of his career.

“Financially, ICI is one of the most successful research centers on campus,” says Dean Jean Quam. “More than that, though, it’s just an exciting place because it brings together multiple research programs with overlapping commitments to improve the lives of people….” In a sense, innovation has been rooted in the institute’s history from its inception. Its founders wanted to produce research and provide training and education from an advocacy perspective centered around the individual. It was a novel approach compared with the more typical clinical model that sees people with intellectual and developmental disabilities as patients in need of a cure, with professionals in control of decision-making.

ICI leaders and staff view disability through a social lens, where the problem to solve is found in how society perceives and treats people with disabilities. Many of ICI’s staff bring added passion to the work through their personal experiences living with disabilities or their insight as family members.

As ICI’s new director, Amy Hewitt is building on that advocacy legacy by diversifying the institute’s funding base, expanding collaborative partnerships, and exploring ways to change the wider community to be inclusive of people with disabilities.

ICI organizes itself around four broad areas of focus: early childhood development and intervention, educational policy and practice, community living and employment, and global disability rights. For each of those areas, ICI staff conduct research, demonstrate effective interventions, and conduct outreach and technical assistance. The institute also develops training and education programs that train community members, organizations, and graduate students. Entrepreneurial ventures are aimed at improving classroom performance, lowering student dropout rates, engaging families, and creating a more inclusive environment for people with disabilities throughout their lives.

Starting early, reaching out

Early intervention in autism and other developmental disabilities can make a significant difference in children’s lives. Pediatric residents, parent groups in culturally diverse communities, and developmental specialists all collaborate with ICI staff to create better outcomes.

“Engaging communities is interwoven in everything we do,” says Jennifer Hall-Lande, research associate, director of several ICI early-intervention programs, and project director for the Minnesota-Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network (MN-ADDM). MN-ADDM has expanded ICI’s reach in recent years, partnering with the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control on early intervention awareness, in addition to its widely quoted studies quantifying the prevalence of autism in the Minneapolis area and in certain ethnic communities.

Another important partnership has been with La Red, the Latino Childcare Providers Network, which has worked with ICI to develop training materials and provide screening to spot early signs of autism. The team has also done considerable work alongside the Somali community.

“We’ve always viewed this work as bi-directional,” says Hall-Lande. “We bring our experiences and knowledge and then we learn from underrepresented communities how to better work together and how to build trust.”

The approach has resulted in deeper relationships that are now leading to further grant-supported work, says Rebecca Dosch Brown, an ICI coordinator who works on a number of the institute’s projects.

“The positive outcome has been that we’ve been able to continue to build relationships in the community,” she says.

Making education more inclusive

ICI is raising expectations for classroom achievement.

“Students with the most significant cognitive disabilities remain the most excluded students across the country,” says Terri Vandercook, assistant director of the TIES Center, part of ICI’s National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO).

Launched in 2017 under a five-year, $10 million commitment from the U.S. Department of Education, TIES works to increase Time, Instructional effectiveness, Engagement, and state Support for including K-8 students with the most severe cognitive challenges more fully in the educational system. After a competitive process, the state of Maryland was selected last year to work with ICI and others to lift the inclusion conversation to the state’s highest levels of educational leadership.

“We’re trying to have a systems-change approach to this whole issue,” says Vandercook. “When we first started working with individual students and teachers, we did it one at a time and created some awesome outcomes for those individual students and their peers. It was a place to start, but it wasn’t going to change the system and that’s not acceptable. We are now going to connect the district and state levels with classrooms doing this work so they are helping one another identify opportunities and challenges.”

One of Hewitt’s highest priorities since taking the leadership role is cultivating relationships with potential partners in grant work as well as diversifying ICI’s staff. This is being done though ongoing Diversity Fellowships and the Minnesota Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and related Disabilities (MNLEND) program. MNLEND develops future leaders in the neurodevelopmental field and has now graduated more than 200 fellows from diverse cultural and professional backgrounds, deepening ICI’s ties in schools, healthcare settings, and the wider community.

Meaningful work, meaningful life

ICI investigators are pursuing new ways to create opportunities for fulfilling work and inclusive community life once students leave school-based programs and face their adult futures.

Beginning in the late 1960s, a movement away from overcrowded, dehumanizing institutions to inclusive, community-based homes and apartments began for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (IDD), driven by the belief that they had the same right to a good life as everyone else. A similar trend is happening in the workplace, says Kelly Nye-Lengerman, a research associate focused on community and workplace inclusion issues for adults with IDD. Rather than employing these adults in segregated workshops at substandard wages, advocates today increasingly are working to place them in fully integrated workplaces.

“Some of these concepts are very modern,” she says. “As a society, we haven’t been thinking about people with developmental disabilities having meaningful careers and being self-sufficient. Now, that’s changing. Employment is a primary way out of poverty and ICI is in a unique position to help.”

ICI provides technical assistance and training for employers, and studies best practices to find which supports lead to the most success on the job.

Going global

ICI’s global reach extends to programs in Eastern Europe, India, Zambia, and Bhutan, among other countries, with significant work in developing textbooks, curricula, and job-training programs.

Investigators from the institute’s Global Resource Center for Inclusive Education work with teachers, administrators, and communities to learn and share information about disabilities in a global context. Their International Institute on Progress Monitoring, for example, develops tablet-based tools in multiple languages that help teachers assess the skills of students with significant cognitive disabilities.

“Each country has its own history and legislative path in how children with disabilities are educated,” says Renáta Tichá, the center’s director. “We try to respect that and let it mold our thinking as to how to present learning strategies at the level they want it to be.”

Another example is in the notion of self-determination, said Brian Abery, ICI’s coordinator of school-aged services. In a U.S. context, an independent adult living away from extended family is considered an important goal, but it’s less so in other cultures.

“If the cultural standard is three generations of families living together, telling the parent of someone with a disability they need to now push them out to an apartment is not culturally appropriate,” Abery says.

Staying on the cutting edge

Some of its early work established ICI’s national footprint decades ago, such as longitudinal studies charting federal and state services provided to people living with IDD. Now, newer, more entrepreneurial ventures, including online training for direct support professionals providing support to people with disabilities and web-based apps that monitor student progress, are extending ICI’s outreach.

Partnering with publishing company Elsevier and several universities and organizations across the country, the institute has offered DirectCourse since 2001. DirectCourse is a suite of online curricula that trains direct support professionals (formerly called caregivers) to better serve older adults and persons with disabilities. Last year, more than 402,000 learners enrolled in these courses. Through projects like Self-Advocacy Online, the institute’s Research and Training Center on Community Living is translating key knowledge about topics like self-determination and justice into simple language with engaging video and animation, free of charge.

Web-based tools for mentors to track student outcomes and progress are available through Check & Connect, a highly successful high school dropout prevention program begun in partnership with the Minneapolis School District in 1990. The program matches students at risk for truancy or dropping out of high school with adult mentors, who both advocate for and challenge their students to achieve more.

The National Center on Educational Outcomes also plays a leadership role in measuring academic progress of English learners and students with disabilities. Building on that history, the center recently launched interactive training courses, known as the DIAMOND project, that equip teachers with online guidelines for deciding which accessibility features are working or not working for individual students.

“We’re asking the research questions that are vitally important to people in our communities,” says Hewitt. “We have researchers working on new projects across the lifespan and longitudinal research that’s been going on for decades.”

One of ICI’s other great strengths is meeting people where they are, acknowledging their perspective, and then delivering meaningful training and support. These qualities are in high demand today as educators learn to work with digitally native students, Quam says.

“Students want information in an on-demand format and ICI does just-in-time education so well. It’s really a model for the future, and now they are not only nationally recognized, but internationally recognized for the work they are doing,” she says.

Moving forward

Despite all of its progress, much work still needs to happen for ICI to realize the dream of full inclusion for people living with disabilities. There are still too many students with disabilities sitting on the sidelines of class participation. Employment rates among adults with disabilities are very low. There is still much to learn about cultural differences in autism prevalence and intervention and disparities in service utilization. These are just a few of the remaining challenges.

“What’s also still very real, though, is ICI’s commitment to challenging assumptions along the path to justice for persons living with disabilities,” says Hewitt. A once-radical notion in those early days at Pattee Hall about people with disabilities having just as much inherent worth as anyone else echoes today in ICI’s current work. Through applied research, hands-on and online training, cultural outreach, and international exchanges, those efforts now reach deeper than ever into the wider community, calling on people of all abilities to value one another’s diversity.

Coordinator John Smith came to ICI in 1996 after working for 10 years as an advocate for people with disabilities.

“ICI was about research and showing what was possible,” he says. Twenty-six years later, and it has become his life’s work. “I love and continue to love that marriage of science and advocacy.”

“And what I love most about ICI is that we’re nimble and have the kind of culture that thrives when we’re trying new things,” Hewitt says. “We have exceptionally committed people who see themselves in our mission.”

Story by Janet Stewart | Winter 2020

Read more about the Institute on Community Integration. Please support ICI by making a gift.