News

Called to serve

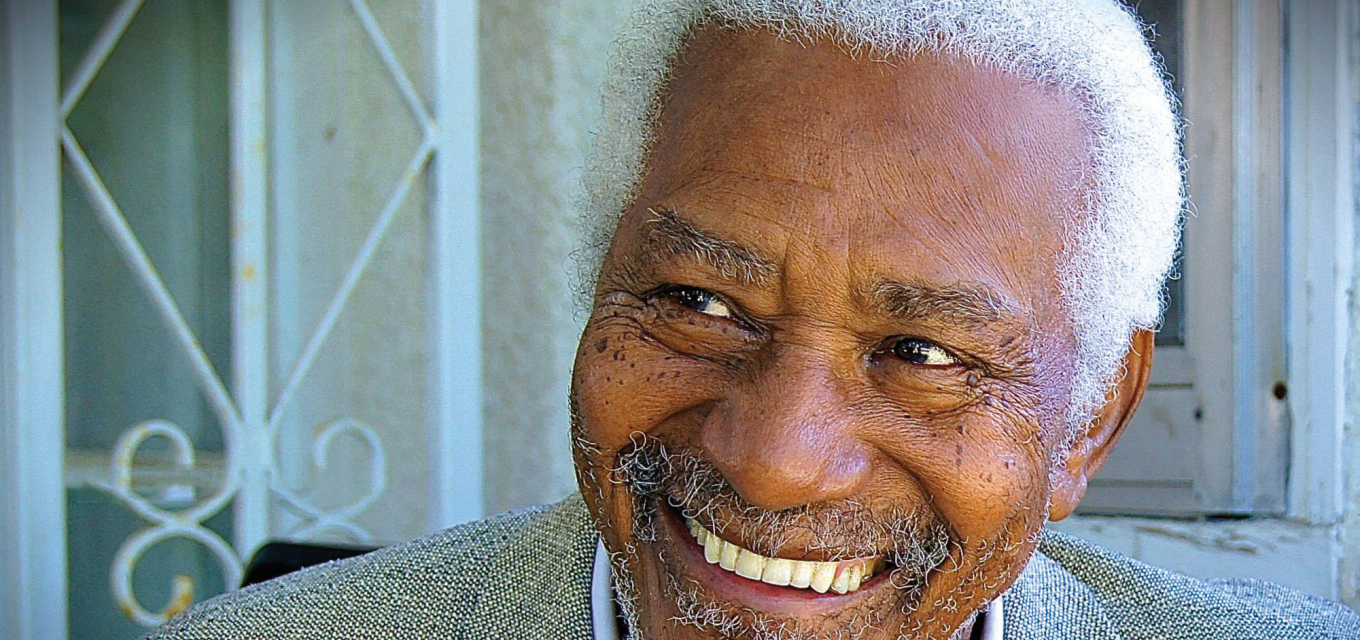

Frank B. Wilderson, Jr. revolutionized special education, diversity, equity and inclusion, and mental health services at the U and across Minnesota.

Certain people we meet in our careers leave an indelible impression. For Emeritus Professor Frank Wood—and many others across CEHD, the University, and state of Minnesota, Frank Wilderson is that colleague.

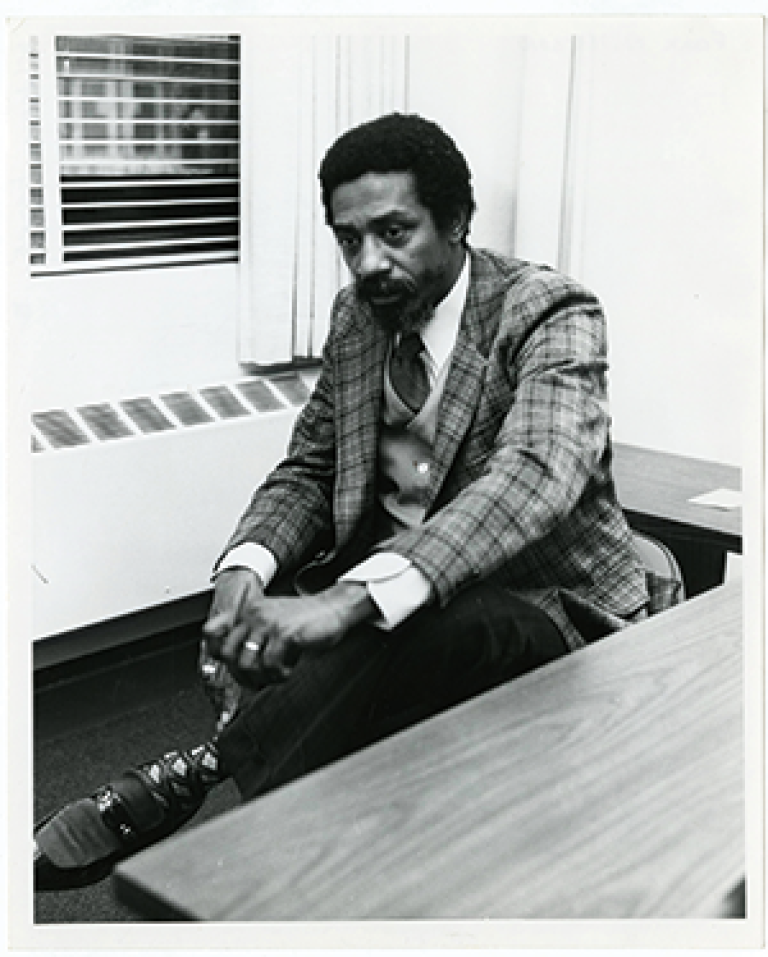

“Frank was the first Black tenure-track professor at the University. He pioneered in places where people were all-too-ready to see him not succeed. There was pretty overt racism on this campus in the 1950s and 1960s. He did a good job, and did so with real courage, grace, and modesty,” Wood remembers.

Establishing teaching licensures for EBD and the IEP

In 1962, Wilderson earned his PhD in educational psychology at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor, where he had been working on a grant to support children with reading difficulties. He and Dr. John L. Johnson—then a doctoral student at Michigan State University—also started Michigan’s first-ever Council for Exceptional Children Division focused on children with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD).

After his graduation from the University of Michigan, Wilderson joined the University of Minnesota’s (then) College of Education as an assistant professor of educational psychology. At the time, Minnesota had just passed legislation to help fund licenses for teachers of children with EBD. Wood was a doctoral student working on the training program, and as part of the program, was teaching the first special education class for children with EBD in Minneapolis schools.

Working together on the training program and sharing an office in Pattee Hall, Wilderson and Wood became fast friends.

Not long after he started at the U, Wilderson was called by the College of Education’s Dean’s Office to run the Urban Education Program. Funded by the Office of Teacher Education (OTE), the program trained existing elementary education teachers in disciplinary techniques for students with EBD.

During this time, Wilderson and Wood, now a tenure-track professor himself, continued to work together. The professors ran a psychoeducational clinic in Pattee Hall. There, they worked with parents, students, and teachers on an early Minnesota version of what would become the Individualized Education Plan (IEP), which special education teachers use to support students to this day.

Looking back, Wood describes Wilderson’s mark on the field of special education.

“He always was a clinician in addition to teaching and research,” Wood says. “That research and practice brought him to the U. Frank was the leader. He was the person who really developed the EBD program.”

Founding the African American Studies Department

His psychology and education background may have brought him to the U, but the longer Wilderson stayed, the more he was called to lead.

On January 14, 1969, he helped make history. About 70 Black students on the Afro-American Action Committee (AAAC) took over the University of Minnesota’s bursar’s and records office in Morrill Hall. They were protesting hostile treatment of Black students on campus and demanding an African American studies department. This protest is now known as the “Morrill Hall takeover.”*

“He did a good job, and did so with real courage, grace, and modesty.”

The AAAC students called Wilderson to help communicate their list of demands to the President’s Office.

“They had a list of about 20 different demands,” Wilderson recalls. “I told them, ‘The president and vice president are going to take one or two of them, and that will be it. Pull out a few of your highest priority demands. If it looks realistic, that gives them some serious things to consider.’”

Ultimately, the University accepted the students’ demands, the occupation ended, and with Wilderson leading the charge, the African American Studies Department was established by fall. He once again was called to chair the committee that worked to create this new department.

Wilderson recalls looking forward to finishing up his position in the Dean’s Office when, once again, he was called to service. The Office for Student Affairs contacted Wilderson and encouraged him to apply to its VP position. He did and was quickly selected for the role.

For 14 years, Wilderson served as vice president for student affairs, where he oversaw and supported programs and students across the University. At one point, his role temporarily expanded to include oversight of the Athletics Department, as well as the University Police Department.

Advocating for mental health and equity in Minnesota

According to Wood, after his VP role ended, Wilderson continued to find ways to serve his community by supporting those with mental health issues and advocating for equity, often together with his wife, Dr. Ida-Lorraine Wilderson, an administrator in the Minneapolis Public Schools.

He returned to the Special Education Program in the Department of Educational Psychology for 10 years after his VP role with Student Affairs ended, serving as Program Coordinator during that time.

Outside Wilderson’s work at the U, he kept busy as a clinical psychologist. He founded and was chief psychologist for a number of programs.

Wilderson frequently worked with the Minnesota Department of Corrections, as well as with rehabilitation centers, including Turning Point—which has a mission to serve the African American community in Minnesota, beginning with chemical health. In addition, he served as a trustee on the board of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation. There, he served as chair of the Graduate School of Addiction Studies.

Leaving a legacy of service

After 37 years at the University of Minnesota, Wilderson retired in 1999, leaving a legacy of service to the University and his community.

“I never could understand how Frank could keep it all balanced, and maybe he didn’t,” Wood says. “He made amazing contributions, particularly because he was called on all of the time. He wasn’t interested in promoting his own name, but working on what needed to be done.”

Dr. Wilderson’s wife, Ida-Lorraine, passed away in 2019. Today, Frank B. Wilderson, Jr. lives in Minneapolis, along with his daughter, Fawn, who is a special education teacher with the St. Louis Park Public Schools.

Photos courtesy of Bonni Allen, University of Minnesota Libraries, University Archives

Learn more at mnopedia.org/event/morrill-hall-takeover-university-minnesota.

-Sarah Jergenson