50 years of ‘giving away’ early childhood expertise

CEED celebrates milestone anniversary.

Head start was launched in the summer of 1965. Sesame Street premiered in 1969. Early Childhood Family Education was first proposed in Minnesota in 1973. In the 1960s and 1970s, interest in early childhood was growing nationwide. At the University of Minnesota, representatives from several academic departments met with early childhood professionals from the Twin Cities area to brainstorm about the state of early childhood education. Department of Educational Psychology Professor Richard Weinberg, Institute of Child Development (ICD) Professor Shirley G. Moore, and ICD staff member Erna Fishhaut led the effort to organize the activities of staff and faculty whose work touched on early childhood. They established the Center for Early Education and Development (CEED) as an “interdepartmental unit” in 1973 to eliminate barriers to a burgeoning wealth of child development research and best practices coming out of the University. As Weinberg, who later joined ICD faculty and served as a director of both CEED and ICD, was fond of saying, CEED was created to “give away child development.”

In the years that followed, CEED received funding from the University as well as external funders such as the Bush Foundation and helped launch new courses and a master’s program in early education.

CEED staff convened conferences, workshops, and coffee hours; they mailed out publications like the Early Report newsletter; and established a lending library.

Fishhaut became a frequent presence at the state capitol, where she met with legislators and passed out “Fact Find” pamphlets on child development. More than 100 staff and faculty, students, and community members answered CEED’s call to join the conversation around early childhood.

“Looking at CEED’s history, our activities have always been characterized by two things: a desire to share evidence-based information and a desire to collaborate,” says Ann Bailey, director of CEED since 2019.

“Our programs, our modalities, our curricula, those things have changed with the times and with advances in early childhood research. But sharing evidence-based information and collaboration are constants.”

Alignment with state and federal priorities

As the University’s only center for early childhood research and practice, CEED was well positioned to work on implementing federal legislation like the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), first passed in 1975. A shortage of trained special education providers hampered Minnesota’s ability to provide mandated services. From its inception, CEED provided continuing education to educators, health care providers, legal professionals, and others through its Professional Growth Institutes and Career Growth Fellowships. In 1982, CEED used that expertise to establish the Minnesota Early Intervention Summer Institute, which over the next four decades would become a must-attend conference for early childhood special educators.

CEED also helped create a joint licensure program in special education that offered common classes to ICD and educational psychology students.

“A lot of that work was through Mary’s leadership,” says Educational Psychology Professor Emeritus Scott McConnell. Mary McAvoy, professor of educational psychology, was director of CEED from the mid-1990s until McConnell took on that role in 2000. Frequently referred to as “a force of nature,” she was an expert on special education. In addition to work that flowed from IDEA, CEED became a key player in the implementation of Early Reading First in Minnesota.

“What was a federal initiative to promote literacy for preschoolers was really the beginning of Minnesota’s efforts academically and civically to improve our capacity in early childhood programming to support kids’ needs,” says McConnell.

“There was a shift to being more inclusive and attentive of higher-risk kids and more historically marginalized communities.”

As awareness increased that early childhood programming could influence later academic and social-emotional outcomes, so did interest in improving early childhood program quality. In the 2010s, CEED established a program conducting classroom observations and assessments. CEED also developed curricula for child care providers, some of which became online courses in Minnesota’s then-nascent training database, now known as Develop.

CEED was involved in establishing Minnesota’s first quality rating improvement system, which today is known as Parent Aware, and the legacy of these efforts is still a major part of CEED’s work. Today, CEED’s team of trained observers helps determine program quality ratings for child care providers who participate in Parent Aware. They also train classroom observers and coaches who work with child care providers. Since 2021, the statewide Trainer and Relationship-based Professional Development Specialist Support (TARSS) program has been based at CEED. TARSS staff support child care trainers and relationship-based professional development specialists who work with licensed child care providers throughout the state. They even teach trainers to originate and develop their own trainings for early childhood educators. Minnesota’s early childhood ecosystem is vital and complex, and CEED expertise is tapped to strengthen it throughout.

A growing focus on relationships

In 1995, Christopher Watson joined CEED to take on the position once filled by Fishhaut. (He would stay on at CEED until he retired in 2021, in capacities that included co-directorship of the center with Amy Susman-Stillman from 2008 to 2015.) Watson worked directly with early childhood educators and heard from them about the challenges they encountered.

“It was a real wakeup call for me to understand that there were kids who were so traumatized and so dysregulated that they behaved in ways that made their caregivers afraid to come to work,” says Watson. “For care providers, it’s not only about the physical impact of violence, but also taking all of that home with them emotionally.”

Watson wanted to help early educators support the children in their care, but he also wanted to understand how the educators themselves might best be supported. One promising technique was reflective supervision. Through regular group sessions or one-on-one meetings, reflective supervision encourages frontline professionals to explore work challenges through the lens of relationships, and there’s evidence it helps improve effectiveness and mitigate burnout.

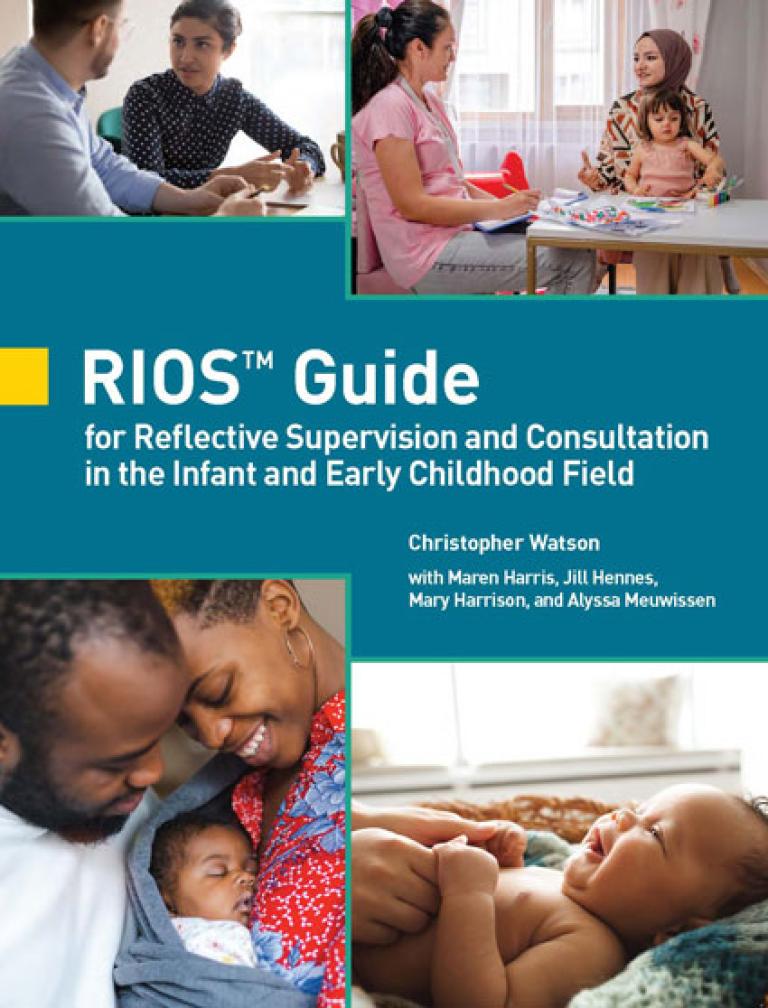

In 2011, with colleagues at CEED and elsewhere, Watson began developing the Reflective Interaction Observation Scale (RIOS) to measure the “active ingredients” that make reflective supervision work. Although the RIOS was created for use in research, practitioners immediately adopted this unique tool to guide actual reflective supervision sessions. In 2022, Watson, along with CEED’s Alyssa Meuwissen and others, published the RIOSTM Guide for Reflective Supervision and Consultation in the Infant and Early Childhood Field to help them do just that.

“CEED was very important, and it’s continued to be,” says Weinberg. “It’s mushroomed now into all sorts of wonderful activities far beyond what we did. It’s giving away workshops, printed materials, and more. I take such pride in seeing what CEED has become.”

From three paid staff members in 1973, CEED—now administratively housed as a center in ICD—has grown to 14 full-time and several part-time staff under Bailey’s leadership. The center contributes to the early childhood field not just through traditional in-person training and events, but also through online learning that allows people anywhere in the world to access CEED’s unique expertise. Outreach to practitioners continues through an active blog, email newsletters, and a newly refreshed series of research-backed tip sheets discussing urgent topics from trauma and resilience to authentic assessment.

Some of CEED’s current projects include leading the revision of Minnesota’s Early Childhood Indicators of Progress (early learning guidelines that describe what children should be able to do before kindergarten), studying a pilot reflective supervision program for county child welfare workers, and partnering with the Greater Minneapolis Crisis Nursery to update and publish their in-house training curriculum.

Long-standing partnerships with state agencies have allowed CEED to have an impact at the state level. Meanwhile, collaborations within UMN have yielded results such as an online library of professional development resources (cd4cw.umn.edu) for child welfare workers co-created with the Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare and the Building Family Resiliency podcast (ceed.umn.edu/building-family-resiliency) co-created with the Institute on Community Integration. Most recently, Bailey and Elizabeth E. Davis, associate professor in the Department of Applied Economics, were awarded a four-year grant from the federal Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation. Bailey and Davis will study the impacts of subsidies on providers’ and families’ participation in child care assistance programs.

Kerry Gershone works with CEED as professional development policy and implementation specialist at the Minnesota Department of Human Services.

“People at CEED have a certain je ne sais quoi that combines professionalism, passion, and compassionate humanity,” she says. “Often when we meet, in addition to discussing our agenda items, we’ll discuss important issues facing the field, how we approach our work, and best practices in providing high-quality education to both adults and children. I know that this content isn’t just work for CEED employees, it’s also their passion and area of expertise.”

Bailey agrees.

“I’m grateful for the people who have chosen to bring their talents, their curiosity, and their drive to CEED,” she says. “They show up every day excited to advance the early childhood field and ultimately, to have a positive impact on the lives of early childhood professionals and the children and families they serve.”

Photo credit(s): CEED

-HANNAH BAXTER