News

Providing Mental Health Care in a Humanitarian Crisis

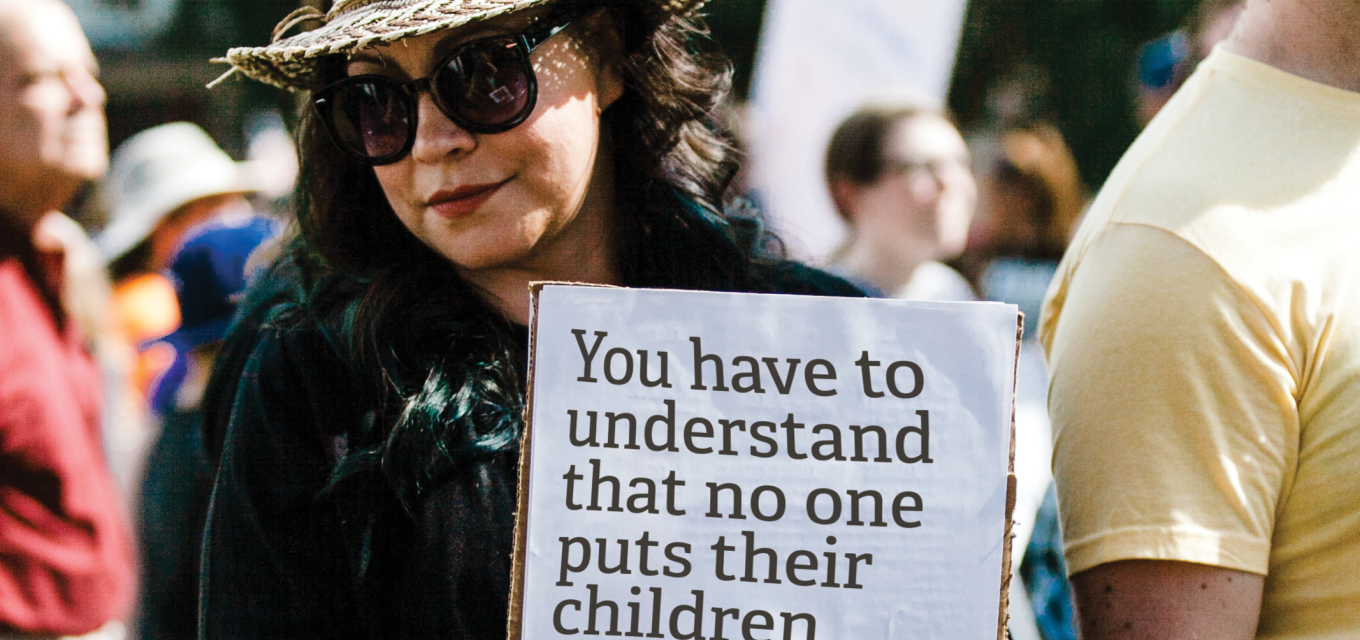

For School of Social Work faculty member Katrina Cisneros, those lines from Warsan Shire’s poem, “Home,” eloquently explain why thousands of refugees are willing to risk their lives to seek asylum in the United States and why she wants to do whatever she can to address the inequity of access.

She was paying close attention in the summer of 2018 when the news stories started to come out about asylum seekers being detained at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“You only have to sit in a shelter for five minutes and hear people’s stories to understand that they are highly vulnerable people who have left extremely dangerous and volatile situations and traveled thousands of miles to seek refuge in the United States,” and now are required to wait in some of the most dangerous cities in Mexico for a chance to plead their case for asylum, Cisneros explains.

She is a licensed independent clinical social worker who has worked for a number of agencies in the Twin Cities providing individual and group therapy and clinical supervision. She also is fluent in Spanish and has expertise working with chronically stressed families, including those from numerous Latin American countries.

Despite her qualifications, she found it difficult to find a way to gain access to the U.S. detention centers, until this spring, when she learned about a local team, led by Dr. Miguel Fiol from the University of Minnesota Medical School, that had traveled to Mexico in January to provide care to people in the refugee shelters in Tijuana, Mexico.

While the need for medical care is obvious, Cisneros says, the mental health component is often neglected because it is so complex and difficult to manage. She sought out the two members of the January group, Sarah Lechner and Roberto Lopez Cervera, who had focused on trying to provide it. By the end of the trio’s first meeting, Cisneros—whose energy and passion are obvious to anyone who meets her—had agreed to take the lead organizing the mental health volunteers for the next trip.

So they began to tackle the big question: How do you provide ethical mental health care in a humanitarian crisis?

They decided that the way to do that was to ensure that their work was anti-oppressive, trauma-informed, and ethical.

Being anti-oppressive means approaching the work from a multi-disciplinary approach with humility and is aimed at dismantling socioeconomic oppression. Trauma-informed care practices promote a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing, which is the best way whether or not the therapist knows the person they are working with has suffered trauma. Ethical means ensuring informed care and informed consent.

“I needed to make sure that anyone who wanted to speak with me knew who I was, where I came from, what my role was, and that, given the inevitable nature of the crisis, they may never see me again,” she explains.

Before her first trip to the shelter in Tijuana, she thought a lot about how to introduce herself and explain what the MSW and LICSW behind her name mean.

But when she got down to the shelters and actually sat with the women and children, “what came out of my mouth was ‘I’m Katrina Cisneros, and I’m a woman and a mother.’ ”

She decided the best way to help the women would be to use listening circles, where the women could decide whether they wanted to share a piece of themselves and what they wanted to share. Cisneros’s role was to help navigate the conversation among the women and hold space.

One woman chose to talk about why she had left her home country, and the woman next to her just sat and wept because something about what the first woman was saying touched and honored her own experience, Cisneros said.

“I can’t tell you how many times in these groups women would say, ‘That’s exactly what happened to me,’ or ‘I can’t believe we’ve been in this shelter for a week and we haven’t even talked.’ ”

The connections also helped to build parent-child relationships by getting parents and kids to have fun together doing an art project or building with Legos—anything that wasn’t stressful. That was particularly moving for Cisneros, the mother of three young sons.

“As I sat there in the groups of women, it was incredible to me that not one woman identified herself as the reason she was there,” she says. “It was all about the wellbeing, safety, and future of her children.”

Simple things like recognizing the selflessness and the sacrifice that these women were making for their children was very empowering for them.

Once Cisneros, who herself isn’t a highly religious person, discovered that the women’s spirituality and faith were their strongest protective factors, she ended every circle with a prayer. In one group, a woman volunteered to pray aloud, and, as she prayed, all of the other women started saying their own prayers under their breath.

“As I closed my eyes and bowed my head and tried to listen to what these women were saying,” Cisneros says, “I realized that most of them were actually praying for me. They were praying for my safety, they were thanking God that I had come to be in the shelter with them, they were praying for my children and my safe return to a country that they themselves were aching to arrive to. It was just really, really overwhelming.”

As she teaches full-time in the social work program, Cisneros continues working on getting more mental health providers to Mexico. The local psychologist who runs the clinic she was working with in Tijuana asked her to consult on the mental health committee of the Refugee Health Alliance, so she is helping develop a program to give more structure for volunteer mental health workers.

“It’s not just about having warm bodies that can talk to people,” Cisneros says. “You have to make sure that the volunteers are trained, that they’re licensed, that they have the skills necessary to meet the population that they’re going to be working with.”

Locally, she is working with the two volunteers she met last spring to develop what they are calling the REACH (Refugee Empowerment and Community Health) project. They want to make REACH a hub for organizing local practitioners who want to go down to the border.

In July, she presented a webinar sponsored by the Center for Mental and Chemical Health, which is housed in the School of Social Work. A record 400 people signed up for the event.

“Since doing the webinar,” she says, “I’ve just been inundated with local providers, activists, and people here in our own community who work with local people seeking asylum. There’s thousands here in Minnesota and the Dakotas. The REACH project is trying to think about how to harness all of this interest and energy and potential into something cohesive.”

Recent raids on immigrant communities in the United States have left a lot of people struggling with fear and anxiety. REACH leaders are considering providing workshops for local communities that need mental health support.

“I said this in the webinar,” Cisneros says, “the women that I’m sitting with in Tijuana are the same women and children that are here, it’s just they’re on a different place in the journey. And everyone counts, and everybody’s story matters, and everybody’s need is important. And so I’m trying to sort of straddle both of those aspects of the work. How do I now stay connected and helpful down at the border with program development and trying to support this volunteer effort, while also making sure that the grass in our own backyard is tended to?”

And, because she is a teacher, she is trying to develop a curriculum to turn the situation into an experiential learning opportunity for the School of Social Work and its students that deconstructs power and oppression at the border and is also focused on the social location of the student.

“I have a million ideas, things that students could experience or do in this humanitarian crisis that would feel meaningful and would enrich learning and bring textbooks and theory and concepts and evidence-based practices and interventions—all of these words that we use—to life.”

On her last trip in July, she said, she thought a lot about her students. “I was thinking, this is it; this is social work; this is relevant. This work embodies who we are as a profession, who we want to be as a school, and who so many of my students want to be as a social worker.”

Story by Jacqueline Colby | Winter 2020

Read more about Katrina Cisneros and her work.