2024 Winter

Ambiguous loss: when closure doesn’t exist

How Pauline Boss’ groundbreaking theory changed our view of loss.

Sometimes people call Dr. Pauline Boss a grief expert. She always corrects them.

“I’m not a grief expert,” she says. “I’m a loss expert.” Loss leads to grief, she explains, but in the case of a missing person, for example, the ability to grieve is frozen. You are immobilized waiting for clear information which may never come. “You don’t know if that person is alive or dead,” she says. “People can’t grieve; they are stuck. Thus the theory of ambiguous loss is about stress, a deep, deep stress that without certainty, may continue for a lifetime.”

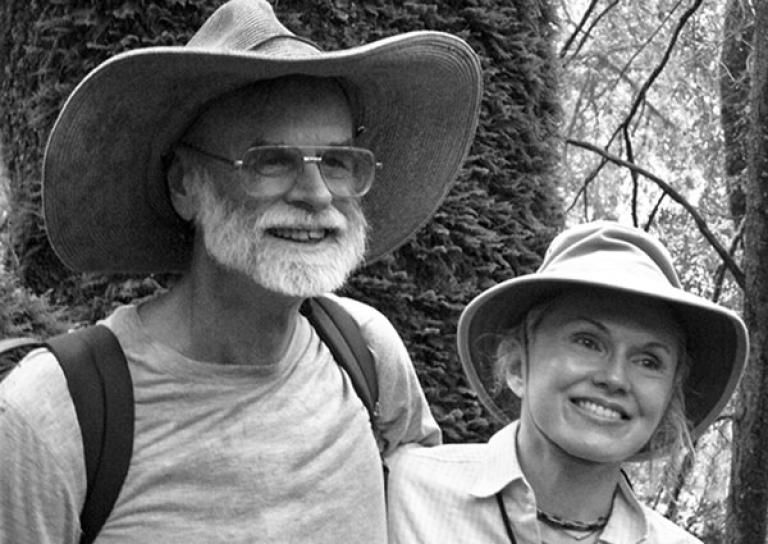

Boss, a professor emeritus in the Department of Family Social Science, has spent nearly 50 years studying this phenomenon of ambiguous loss, a term she coined in the 1970s. Ambiguous loss describes a loss that remains unclear and thus has no resolution. It leads to feelings of confusion, anxiety, and chronic sorrow.

Pauline Boss has helped people across the world cope with the grief associated with loss through her development of ambiguous loss theory and its translation to clinical, community, and research-based settings.

Learn how you can help honor and continue Pauline Boss’ legacy.

To help guide people living with ambiguous loss to a steadier ground, Boss has practiced family therapy, trained fellow therapists, written numerous books, and expanded on her theory, which has become recognized throughout the world.

David Olson is a fellow professor emeritus who has known Boss for nearly 40 years and has observed her work up close.

“One significant characteristic of her academic work is that it bridges theory, research, and practice—what I call the ‘triple threat,’” he says. “This means that her ideas are theoretically sound, empirically validated, and relevant to helping individuals, couples, and families. Her major contribution to the family profession and to individuals, couples, and families has been the development of the concept of ambiguous loss. May her ideas continue to enhance the lives of those under stress around the world.”

Identifying ambiguous loss

Boss’ professional work in ambiguous loss first took root in graduate school, but the antecedents can be traced back much further than that. She jokes that she listened to the popular radio detective drama Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons growing up in the 1930s and 40s. “But I think there’s a bigger reason I’ve stayed with this topic,” she says. “I’ve always had a love of family.”

Boss grew up on a farm in New Glarus, Wisconsin. She was one of four children in an immigrant Swiss family. She remembers her father receiving letters from relatives back in the homeland. Sometimes the letters had a black border—signifying a death in the family. Even though she didn’t know the Swiss relative personally, she could still feel a sense of loss through her parents. Immigrants by their very definition have ambiguous loss baked into their identities. As they move from one place to another, a part of their lives is missing.

“Even if it is a voluntary immigration, you have lost something,” she says. “You have left something or someone behind.” That is a common kind of ambiguous loss.

As Boss entered the 1950s, there weren’t a lot of choices for women in college, but a combination of a love of reading, a desire for scholarly pursuits, and a streak of curiosity motivated her to seek her own path. She enjoyed teaching so she earned a degree in education from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She later became a family therapist and went back to graduate school to focus on marriage and the family. As she sat in on therapy sessions with families of troubled children, she noted the fathers were always angry about being there. “Fathers thought their role was to earn a living. They would say ‘Why am I here? I need to be at work.’” she says. “The families had a father, but they all said that the kids were mothers’ work.”

The fathers were psychologically absent but physically present in the family. Although this was the first kind of ambiguous loss Boss studied, it is now known as Type Two: psychological absence with physical presence. This can occur when the individual is emotionally missing, such as the 1950s fathers, or anyone who is cognitively gone, such as those afflicted with dementia, traumatic brain injury, mental illness, addiction, or any condition that takes away one’s mind and memory.

The other kind of ambiguous loss, Type One, is defined as physical absence with psychological presence. Examples include kidnappings and those missing due to wars, terrorism, and natural disasters.

Losses stemming from divorce and adoption are more common examples of Type One, as well as the loss of physical contact with families due to immigration—the feeling Boss’ parents had when they received those black-bordered letters.

Boss researched Type One in the early 70s when, for her doctoral dissertation, she studied the wives of men missing in action in Vietnam and Southeast Asia. It was then when she came up with the term ambiguous loss. “What I did was provide a name for a type of loss that’s been common but had not been acknowledged,” she says. “Giving this stressor a name helps people begin to cope with it.”

“It’s amazing she coined this phrase that we never knew how to approach before,” says journalist and author Krista Tippett, who hosts the popular On Being podcast. “Ambiguous loss has filled in such an important part of the puzzle for us.”

Tippett is an expert on moral wisdomand human understanding. She notes that Americans in particular focus so much on closure and moving forward, but that is actually not how people function. “Loss is a condition of being human,” she says.

“Pauline has been able to help us understand this particular source of pain. Its biggest strength is taking seriously the fact that uncertainty is the reality much of the time, but we have to go on living.”

Boss was a featured guest on Tippett’s podcast in 2020 during the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘She was a lifeline’

January 28, 2024, marks 17 years that Donna Carnes has lived with ambiguous loss. Her husband, famous computer scientist Jim Gray, disappeared while sailing off San Francisco Bay. Neither Gray nor the 40-foot vessel Tenacious were ever seen again.

“We suffered from the extreme end of ambiguous loss,” Carnes says. “We don’t know what happened. There is not one single clue as to what happened to Jim. It was a vanishing. This extreme type of ambiguity is very hard on people because you don’t have even one ‘maybe’ clue to try to shape a story or idea around.”

Carnes was skiing in northern Wisconsin with some friends when she heard the news. The Coast Guard set up a massive search, but extensive effort both above and below the water turned up nothing. “Frankly, a sailboat is a needle lost in a haystack,” she says.

Traditional support groups were not a good fit for Carnes since she had such a unique loss. Through a childhood friend, Carnes heard about Pauline Boss and her work and contacted her via email. In May of 2007, Carnes came to Minnesota and met with Boss over three days.”

“She was a lifeline,” Carnes says. “I come from a scientific community and it’s hard to get our head around that we don’t have a solution to a problem.” Carnes recalls talking to people who didn’t know how to communicate with her. “A friend of Jim’s turned beet red and walked away from me,” she says. “He couldn’t talk to me. He felt so bad for me but he didn’t know how to handle it.”

Carnes met with Boss regularly for some years. “A practical jewel of wisdom I got from her was ‘don’t let anybody in any way pressure you to have an ending to this you are not comfortable with,’” she says. “People make up their own endings. I finally said to people, ‘You can make up an ending for Jim, but I don’t have an ending for Jim.’”

The biggest gift Boss gives is the understanding that a person can still have a life, Carnes says. “You can have ‘yes, he may be here’ and ‘yes, he isn’t’ and still be comfortable having a life with meaning. All these years later I still feel married. I asked Pauline if that was normal. It was very normal.”

Today, Carnes is retired from start-ups in Silicon Valley. She regularly travels between Madison, Wisconsin, and San Francisco with her two greyhounds. She likes writing poetry and she still skis. She and Boss coauthored an article called “The Myth of Closure,” from which Boss wrote her most recent book. “When I talk about ambiguous loss, I do all that I can to honor Pauline, because she is so helpful,” Carnes says. “And if talking about it can help other people—well, I would be grateful if anything I said could be of use for anyone who is walking that path.”

Pauline: a very knowledgeable lady friend

The late local theater legend Dudley Riggs, a longtime friend, introduced his wife, Pauline Boss, to me decades ago at the “original” Guthrie Theater designed by Ralph Rapson. Over the years, Pauline, Dudley, and I would meet in various restaurants and attend many theater shows. These were the days when things were fun, interesting, and busy. Fast forward to 9/11/2001. A terrible, unforgettable date. Shortly after 9/11, the NYC Twin Towers President of the Local Service Employees International Union contacted Pauline.

This began a truly historical learning curve in NYC. With Pauline’s leadership, grief counselors and union staff members counseled families who had lost (or not) loved ones. Were people lost in the Twin Towers or surrounding area, were they dead, or alive walking around shocked, lost, or running away? Ambiguous loss, no closure. Grief counseling, under Pauline’s leadership, was invaluable, and is to this day.

In 2004, Pauline invited me to attend “An Evening Honoring Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton and Professor Pauline Boss for Their Critical Help in Healing Families and Communities in the Aftermath of September 11th.” The event took place on July 23 on the 60th floor of Chase Manhattan Plaza, overlooking NYC.

It was a rainy evening. We heard many heartfelt stories that night; including the loss of loved ones, the loss of friendships, and the many friendships made among those grieving during the healing process, and their future of dealing with ambiguous loss. After the program, Pauline introduced me to a family she had helped. They briefly shared with me their journey. With them was the cutest little girl, with the cutest little dress and a big smile. The family was on its way to healing. I will never forget the little girl and her family. They all loved Pauline.

Our wonderful friendship continues to this day. We were recently together, with Pauline’s family members, to celebrate the ribbon cutting of Dudley Riggs Brave New Workshop on Hennepin Avenue in Minneapolis. We regularly enjoy dinner and attending opening night shows at the theater. It’s a true pleasure to share time with a very knowledgeable lady friend.

— Jane Mauer

President, Butler Properties, LLC

Pauline Boss family friend

Six pillars of coping

As Boss expanded on her theory, she looked for ways to help people mitigate the distress caused by ambiguous loss. She borrowed ideas from Eastern cultures which have a higher tolerance for ambiguity. She worked with many people with missing loved ones who have gone on to have relatively stable lives with some joy in them. “I was curious as to how they do that,” she says. “It was difficult and surprising for me because I like certainty.”

Boss did find some answers by studying families, for example after 9/11, to devise six guidelines for coping with ambiguous loss. “They are not linear,” she stresses. “It’s messy.” Boss recalls the five stages of grief developed by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross who wrote in her last book that she never meant for the stages to be thought of as a straight progression from denial to acceptance. Kübler-Ross came to regret that they were interpreted that way in the public’s mind.

Boss’s six guidelines to help people build resilience to cope with ambiguous loss are presented in a circle, and in no particular order. (See Figure 1) They are:

Finding Meaning is all about making sense of the loss and finding a new purpose. For example, a mother turns the tragic experience of her missing son into campaigning to change legislation and working globally to prevent kidnapping and sexual abuse in other families.

Adjusting Mastery is about recognizing your degree of control in the situation. “If we like control, we need to lower it,” Boss says. “We may have to live with not knowing for years, decades, or a lifetime. During the pandemic, people could not control the virus. It was no accident that so many people were baking bread. While they could not control the virus back then, they could control the baking of bread and the certainty of an outcome that was comforting.”

Reconstructing Identity is how a person comes to understand their new identity. “Who am I now that my husband has been physically missing for 20 years? Am I still married? Or with Type Two ambiguous loss, can I have a relationship with someone else if my mate no longer knows who I am? Yes, you can honor your marriage and also have some social relationships for the sake of your own health,” Boss says.

Normalizing Ambivalence refers to coming to terms with conflicting feelings. When a person doesn’t know if a missing loved one is alive or dead, they often wish for the ambiguity to be over, but then realize that means they are wishing the person were dead. This leads to ambivalence and guilt for having that thought in the first place.

Revising Attachment is recognizing that a loved one is both here and gone. “He may be dead and maybe not. She may come back to the way she used to be and maybe not,” Boss says. “You learn to carry two contradictory ideas in your head at one time.” Loved ones are missing, but you keep them in your heart and mind while you also reorganize your life without their physical presence.

The last guideline is Discovering New Hope. “You can’t just wait for the missing person to come back because that would mean putting your life on hold,” Boss says. “You have to discover something new to hope for. Frequently, the new hope is to help other people avoid suffering from ambiguous loss as you did.”

‘This is how I feel’

When thanked for taking the time for an interview, Ellen Blank says, “Anything for Pauline.” It’s a sentiment likely shared by hundreds of people across the world. A physical education alumna and longtime school administrator, Blank established the Lucile Garley Blank Fellowship in Ambiguous Loss to support rising scholars following in the footsteps of Pauline Boss.

Blank grew up in Roseville and found a strong community in the U’s physical education department. Even better, the program allowed her to participate in sports, a rare opportunity in pre-Title IX days. “One person coached both tennis and basketball,” she says.

After graduating, Blank worked in Roseville in a variety of education roles, retiring as assistant superintendent in the same school district she had attended as a child. Blank kept up with the U of M, one day reading about Boss’ work in an alumni magazine. It was the first time she had heard of ambiguous loss and felt an incredible sense of validation. Blank’s mother, an active community leader and voracious reader, had Alzheimer’s disease and passed away after a long decline. The concept of ambiguous loss perfectly captured Blank’s emotions and experience with her mother’s disease.

After meeting Boss, Blank was sure this was an area she wanted to support with her philanthropy. Taking advantage of a matching program, she established the fellowship in memory of her mother. Blank says, “I have shared Pauline’s book with so many people, and every time, people say, ‘this is how I feel.’ It’s a universal experience, and it’s critical that graduate students continue to build the research and clinical work in this area so others can be helped.”

—Ann Dingman

Worldwide impact

Since Boss developed her theory, it has been applied nationally and worldwide. Ambiguous loss theory helps shape interventions used by the International Red Cross and the Red Crescent (ICRC) with families and communities coping with massive losses after natural and human-made disasters. Boss and her graduate students traveled to New York City to work with families of the missing after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. She also trained therapists to work with those suffering after the earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011 as well as the earthquake in Turkey in early 2023. With ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, pandemics, and natural disasters, there is tragically no shortage of those dealing with ambiguous loss.

“The ambiguous loss framework is being tested around the world in various kinds of situations and contexts. Thus far, it is holding up in different cultures,” Boss says. “However, a theory always needs testing, and there are now two generations of scholars who are doing this testing. I am deeply grateful for that. I hope when I stop working, others will pick up the work on ambiguous loss and develop the theory further.”

Although Boss has had a long and influential career, she considers its highlight to have taken place just last spring. She was invited to Spain to give the keynote address at the World Family Therapy Congress hosted by the International Family Therapy Association. “I was honored deeply by that,” she says, reflecting on delivering it to an audience of international practitioners who have applied and tested her theory all over the world. “It was gratifying and humbling,” she says. “I saw that speech as my swan song. But as you know, I’m still working.”

For more information, including two videos of Pauline Boss’ life and University achievements, visit z.umn.edu/pauline-boss.

with families suffering ambiguous loss after 9/11.

Contributing to Boss’ legacy

Noriko Gamblin, a former development officer at CEHD and now at the Carlson School of Management, was struck by how modest and accessible Pauline Boss was when they first met. “Huge theory, humble person,” she says.

Gamblin was intrigued by the steady stream of small contributions that were made for ambiguous loss research by family members of those lost in 9/11, mainly the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) workers whose bodies were never recovered. Boss’ work with the families of SEIU workers led to a fundraiser in New York City in which she and Hillary Rodham Clinton were honored for their work on behalf of the surviving families. Boss received a discretionary gift, which she contributed to the U of M Foundation to fund research in ambiguous loss.

“It was this fund that I, as a development officer, along with other benefactors and development colleagues such as Susan Holter and Brittany Barber, worked to grow into a faculty fellowship that would bear her name in order to carry on the scholarly work of ambiguous loss,” Gamblin says. Gamblin also feels a more personal connection to Boss’ theory. “Like many people who have straddled two countries and societies—in my case, Japan and the U.S.—I have known and felt deeply the losses that come from having a hybrid national identity that is both and neither,” she says. “It was not until I encountered Pauline’s work that I understood that I was not alone, that it is often the condition of immigrants everywhere, and has been for perhaps all of human history. This understanding was the foundation on which I have tried to reconstruct my existence, and it has been more helpful than I can say.”

As a development officer at the U, Gamblin has encountered innumerable opportunities to give meaningfully. “When I made a professional commitment to try to grow Pauline’s fund into a faculty fellowship, I matched it with a personal commitment to contribute to the utmost of my ability, through near-term gifts and my estate plan,” she says. “I have seen up close what philanthropy can do. My dream is that this fund will grow into the Pauline Boss Professorship in Ambiguous Loss, and from there into a chair, as befits her legacy, both at the University of Minnesota and in the greater world.”

Support the Dr. Pauline Boss Faculty Fellowship in Ambiguous Loss.

Bringing ambiguous loss theory down under

My interest in learning about loss and grief goes back to the early 1990s when I started working as a social worker in the mental health services of Western Australia. I had the opportunity to work with many people who were affected by mental ill health and their family members where I heard stories of unresolved grief. Many said that others around them, even health professionals, did not see their losses as legitimate or deserving of support. The existing theories, skills, rituals, and community support at that time only addressed clear-cut losses. Thus, I began searching the literature to find a more appropriate understanding of the type of loss that I kept hearing about.

I came across Professor Boss’ first publication, Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. I contacted her and as luck would have it, she informed me that she had been invited by St. Andrews Church in Adelaide South Australia to facilitate a workshop on skills training in working with ambiguous loss. I traveled to South Australia where I first met Professor Boss in March 2005. Thus began a journey where I was mentored, supported, and taught about ambiguous loss. I spent three weeks in New York learning and discussing ambiguous loss theory and interventions at the International Trauma Studies Centre where Professor Boss was facilitating a workshop. I had many discussions with her and she helped me liaise with services set up by her and her colleagues following the 9/11 incident in New York.

Following my return to Australia, I was acutely aware of the gap in knowledge and practice of working with people experiencing ambiguous loss and the need to address this gap. I was invited to write an article for the local newspaper. This prompted a lot of interest about ambiguous loss from the general public and health professionals. I was invited by various organizations to facilitate workshops and seminars.

In 2008, I was invited to study toward a PhD degree with an emphasis on ambiguous loss at the University of Western Australia. Professor Boss served as an external supervisor. My coordinating supervisor, who was a professor of psychiatry and had a clinical practice, told me this after reading about the theory in the initial draft of my thesis: “Kanthi, now when I meet with my clients and their families, I remind myself to look at their experiences and stress they are going through, through the ambiguous loss theory.” I was very heartened by this remark.

I completed my PhD studies in 2014. Following completion, those who participated in my research suggested that I convert it to a self-help book. Professor Boss reviewed the draft and gave me feedback and very kindly wrote the foreword for the book. The book, Hopeful Voyager: Navigating Your Way Through the Ambiguous Losses of Mental Ill Health, was launched by the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust in October 2018.

The strengths of ambiguous loss theory are that Professor Boss has synthesized a vast amount of research grounded in her clinical experience and her publications are written in clear, accessible language which demonstrates a sincere respect for client diversity. I have found that the theory and clinical interventions she advocates can be shaped to fit a local culture. I believe that her contribution to society and the world is immeasurable.

— Dr. Kanthi Perera

Social Worker, 2005 Churchill Fellow

Perth Australia

Pauline Boss selected bibliography

The Myth of Closure: Ambiguous Loss in a Time of Pandemic and Change (W. W. Norton, 2022)

Family Stress Management (SAGE Publications, Inc., 2017), with Chalandra Bryant* and Jay Mancini

Accompanying the Families of Missing Persons: A Practical Handbook (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2013)

Loving Someone Who Has Dementia: How to Find Hope While Coping with Stress and Grief (Jossey-Bass, 2011)

Loss, Trauma, and Resilience: Therapeutic Work with Ambiguous Loss (W. W. Norton, 2006)

Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief (Harvard University Press, 1999)

*Professor Bryant holds the Pauline Boss Faculty Fellowship at CEHD. She was featured in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Connect.

-KEVIN MOE