2022 Winter

Instilling the love of scientific inquiry

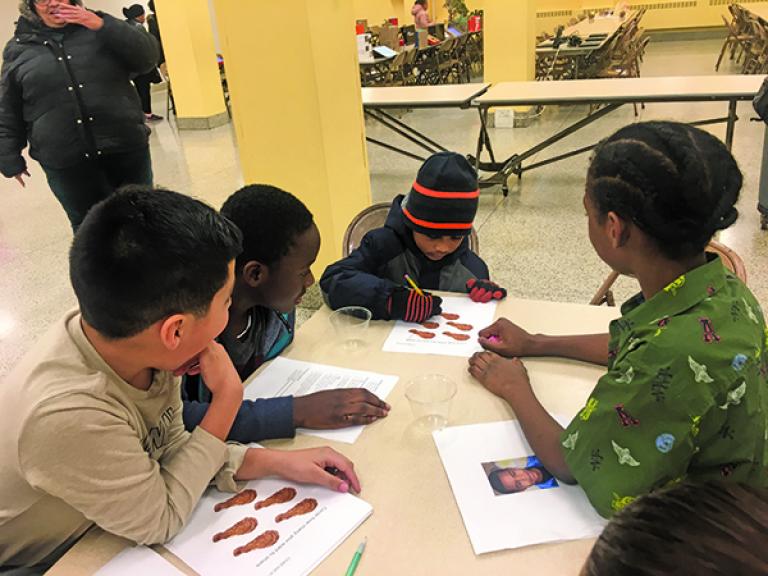

Young scientists program pairs psychology students with middle and high school students to develop a research project.

As Institute of Child Development (ICD) Professor Melissa Koenig tells the story, the program came about for two reasons. Having just returned energized from a sabbatical in 2017, she and her son began mentoring a fourth-grade student from North Minneapolis. As they became more involved in his life, Koenig became involved in his school, Ascension Catholic Academy. When Ascension teachers and staff found out that Koenig studied child development at the U of M, they asked her if there were any programs or initiatives for Ascension students.

At the same time, graduate students in ICD were expressing interest in ways that they might work with communities themselves. “They wanted community engagement opportunities that extended beyond any person’s research lab,” Koenig says. “It occurred to me that there might be something we could offer to Ascension and that became the Young Scientists program.”

Young Scientists is an engagement program where doctoral students from ICD, psychology, educational psychology, and undergraduates from neuroscience all partner to mentor middle and secondary school students as they develop a research project in the field of developmental psychology. “What makes our program unique is we didn’t want to provide instruction or tell them what to do,” Koenig says. “We wanted to give them the tools of scientific inquiry and support them in asking an original question and designing a study to answer that question.”

Koenig worked with then-doctoral student Annelise Pesch to launch the program with Ascension in the fall of 2019. In what Koenig describes as a happy accident, she attended a scientific meeting in Baltimore with the Society of Research in Child Development. “We knew that there was going to be an upcoming meeting scheduled to take place in Minneapolis in the spring of 2020,” she says. “Our goal was that whatever engagement we did with Ascension students, it could culminate in a scientific presentation at this meeting. It would give them a full-blown experience of walking the path of a young scientist.”

“I think it was a fun experience to work with younger scientists and get them interested.”

Pesch, who received her PhD in 2020 and is now a postdoctoral research fellow at Temple University, says the program was a perfect way to interact with a younger generation to spark interest in developmental science.

“It’s been such a pleasure to work with the students, to see how excited they are about developmental science and to hear their amazing and thoughtful research ideas,” she says. “As a first-generation college student, I was introduced to developmental psychology by a college mentor of mine, and I love that the Young Scientists program provides an opportunity to engage and mentor youth in developmental science as early as middle school.”

One of Pesch’s fellow mentors was Andrei Semenov, currently a post-doc researcher in ICD studying executive function brain-based skills that control self-regulation. He had been working on a project with Avalon Charter School, a high school in St. Paul, when Young Scientists was being established and thought the program would be a good fit there as well.

“So when we started, we split the program up into Ascension Catholic Academy and Avalon,” he says. Semenov and a fellow grad student adapted an intro to child psychology college course to present to the high school students and worked with them on designing their experimental projects. One student created a survey to assess the attitudes of truancy among students of her age across multiple schools in the area. She wanted to know if students have different attitudes toward truancy depending on how large their school is. “Large schools might have more acceptable views of truancy because it’s easier to get lost among all the students,” Semenov says. “Small schools would be the opposite.”

The student found the reverse of her prediction. It turned out students in smaller schools had more lenient views on truancy. Regardless, with her findings complete, she created a digital presentation that she showed at a virtual symposium hosted by the Society for Research in Child Development.

“She and the other students who participated got a good taste of what it takes to put out something as simple as a survey and the logistics of contacting schools and managing data after it was collected,” Semenov says. “I think it was a fun experience to work with younger scientists and get them interested. At that age, I wasn’t thinking about child development as part of the sciences.”

Carrie Bakken, a program coordinator/advisor at Avalon, says the Young Scientists program provides valuable real-world research experience. “Our students often use community experts from the field, but the collaboration with the University of Minnesota provided our students with ongoing mentorship and an opportunity to present at a professional conference,” she says. “Avalon teachers would not be able to duplicate this graduate-level experience for our students.”

What does the future hold for Young Scientists? First off, it includes more scholars at Ascension and Avalon designing and doing their own research projects in 2021-22. Seth Thompson, director of outreach for the College of Biological Sciences, plans to shadow the program this year in the hopes of possibly developing a parallel program in another field. Koenig and Thompson are both members of the NODE, a new group at the U of M that is working to make community engagement more accessible. With the support of the NODE, Koenig can imagine the Young Scientist program reaching into more schools, because at its core, Young Scientists is really about community engagement work. “It’s about people who have their ears to the wall of a community in order to meet their needs,” she says.

Learn more at icd.umn.edu/outreach/young-scientists.

Photos courtesy of ICD

-Kevin Moe