News

Responding to the needs of the time

The Department of Family Social Science celebrates 50 years.

From its roots in the “Principles of Economy and Cooking” courses offered in 1884, to 2021 courses such as “Trauma and Resilience in Families,” the Department of Family Social Science has throughout its history responded to the needs of the time. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Minnesota and sent communities into turmoil, FSOS faculty responded with evidence-based advice shared across America in webinars, University-distributed news, and media interviews. From July to December 2020, FSOS current and emeriti faculty did over 50 interviews resulting in over 56 million media impressions that addressed family issues ranging from health care directives to relationship guidance to celebrating holidays on a budget. The department also launched research projects to assess the impact the pandemic would have on families, couples, and their finances. This focus on helping diverse families solve real-world problems goes back to the very origins of the department in the 1970s.

Origins

Officially organized as a department in 1970, Family Social Science throughout its history has grown and evolved in rapidly changing contexts with an ever-present focus on understanding families from multiple perspectives and cultures. The FSOS community’s path has been towards “…being a place where diversity is valued, welcomed and seen as enormously important in making sense and being of help to families.” (Rosenblatt, Interactions, 1995).

America experienced political and societal turmoil in the 1970s—from women’s liberation to social justice to the sexual revolution—and Americans were asking questions, pushing back against social norms, and obsessed with “finding themselves.” In 1970 alone, a Vietnam War protest at Kent State led to four deaths and nine injuries, the My Lai massacre was exposed, and Americans celebrated the first Earth Day.

That same year, Paul Rosenblatt became interim head of the division of Family Social Science in the School of Home Economics after the death of leader Donald Bender. Things were not going well. The powers that be weren’t sure that FSOS should continue to exist, much less become a department. But Rosenblatt—who had just started three months prior—wasn’t giving up.

“They said the department hadn’t been research productive and didn’t have enough students,” Rosenblatt says. His reply? “I can fix that.”

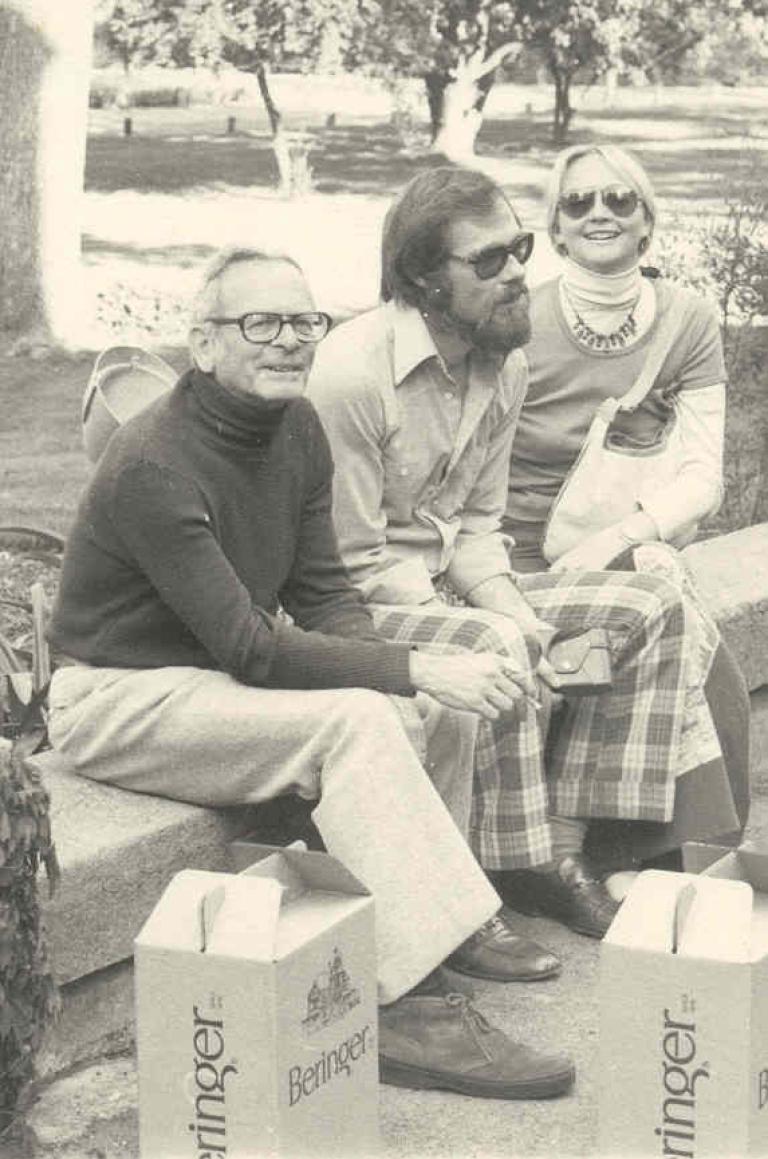

Rosenblatt reached out to Richard Hey, who had come to the U of M to lead a postdoctoral marriage counseling training program in sociology’s Family Study Center (FSC) in 1964 funded by a national grant. However, by late 1969, the grant was winding down. The school hiring committee and administrators were impressed by Hey and wanted to hire him, and Hey set up a marriage counseling training program and assumed leadership of the Family Social Science Department in fall 1970.

Hey had led family life education and supervised counselors in training at the University of Pennsylvania, had been a member of a White House Task Force on Children, and served as president of the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists (AAMFT) and the National Council on Family Relations (NCFR).

“He was a magnet,” says Rosenblatt of Hey, who died in 2015. Described as charming, energetic, and savvy, Hey used his national network and numerous community outreach opportunities to raise awareness of the department.

In a 1995 interview, Hey said, “As department head, I based my actions on three assumptions: it was time to assert that the family is a legitimate subject for academic study; family study is a multidisciplinary enterprise; and family scholars should be well-grounded, well-rounded, and able to understand both research and service.”

Establishing family social science as a legitimate research discipline was their challenge. But they were well-positioned in the School of Home Economics that promoted its inter-disciplinary approach and connections to Extension and the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station that supported FSOS’ applied research focus. As Hey observed…“the family was determinedly treated as contingent. FSOS offered the opportunity to explore some answers.”

Hey moved quickly to recruit his former boss at the FSC, Gerry Neubeck. Neubeck brought his expertise in the areas of marriage counseling and human sexuality to the department and his ground-breaking courses exploring human sexuality and relationships quickly made news.

Family Social Science began to attract students and the number of faculty grew from three to 10 from 1970 to 1977. M. Geraldine Gage and Janice Hogan focused on family economic issues and David Olson came in 1974 to strengthen the department’s educational focus on bridging research, theory, and practice.

A Minnesota native, Olson had been at the University of Maryland and National Institutes of Mental Health where he co-directed a longitudinal study of early marriage and family development. He jumped at the opportunity to return and join a department that was already gaining a national reputation.

Olson also brought his research agenda developing relationship assessments. This research would evolve into the conceptual foundation of a premarital personal and relationship evaluation that would disrupt the field of marriage and family therapy and put the department on the map.

As Hey’s tenure as department head wound down in 1977, he reported in a self-study that FSOS’ next goal was to develop graduate programs because of the sensitivity and commitment that working with families required. He wrote, “…the kind of person our graduate is, is of great importance to us, not just how much knowledge is acquired nor what degree of skill is achieved.”

The material world of the 1980s

Hamilton McCubbin would chair the department from 1978 to 1984. Writing on the FSOS 25th anniversary, he said…“During the seven-year period of my tenure as chair and head, faculty scholarship and focus became the driving force in carving out the role that FSOS would play in the future of family studies.”

The 1980s were a study in contrasts—the rise of Ronald Reagan and conservatism and the growth of personal computers and personal wealth—while an American farm crisis brought on skyrocketing debt, record foreclosures, and bank failures that hit farm families across the nation hard. Supported by Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station grants, FSOS faculty examined the emotional and financial stress that farm families experienced to inform family policy and impact analysis reports.

“Rural families were in real trouble,” says Rosenblatt of the time. “Even listening to students tell their stories in classes brought valuable insights in the research we were conducting.”

Also that decade, FSOS faculty would gain the reputation as the “Minnesota Mafia”—both for their scholarship output and the number of graduates who assumed leadership positions across the country. The department recruited faculty to expand the breadth of family social science research. Another priority was earning accreditation from the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy.

Leading the accreditation effort was Pauline Boss, who came to the U of M from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where she had been developing the theory of “ambiguous loss.” She was pioneering a trail with research and clinical work that would give mental health practitioners new tools to bring relief to those suffering after physical or psychological loss and were not helped by traditional interventions and treatments.

Shirley Zimmerman, Jean Bauer, and Katherine Rettig all would lead significant initiatives that created financial literacy programs and expanded knowledge around the impact that divorce and child support would have on women as well as advocate for family-focused policies.

Hogan assumed leadership of the Department in 1984 and would bring Sharon Danes, William Doherty, James Maddock, and Marlene Stum to the faculty. Danes and Stum had research agendas that explored rural and urban family business issues and the transfer of assets and property. Doherty brought his unique approach combining principles of family therapy and community organizing to develop a model of community-based participatory research. Maddock would bring his expertise on human sexuality and the impact of gender and sexuality on interpersonal relationships in the family.

In addition, Catherine Schultz joined the department in a research support role, while William Goodman, formerly a faculty member in another program, joined to serve as undergraduate program adviser to about 200 students. Cynthia Meyer served FSOS as a senior lecturer and also supervised teaching assistants and undergraduate research projects. All three were instrumental in making the department a special place for students.

Even as nationally conducted surveys listed the University of Minnesota as tops in the field, Hogan says University leaders were pushing FSOS to recruit graduate students and build relationships with universities internationally. She traveled to Thailand and Taiwan to recruit graduate students and arranged for faculty members Cathy Solheim and Dan Detzner to conduct research there.

But the big international exchange opportunity came from alumna Susan Hartman, who had started a non-profit to facilitate sister city agreements and exchanges. CONNECT US/Russia arranged for a FSOS faculty exchange with the USSR Academy of the Sciences in Moscow.

“Susan spent countless hours transporting proposals between Moscow and the U, meeting with scholars, arranging visas, translators, and transportation,” says Hogan.

The exchange began in 1988 with eight FSOS faculty hosting seven family scholars from the USSR to discuss family issues. The goal was to identify family issues on which they could all agree for a book comparing them from both perspectives with the utmost diplomacy and equanimity.

“The communist system stressed equality, but men were clearly in charge,” says Hogan. But she said when it was clear that the U.S. contingent would be four men and four women, the Soviet exchange leaders scrambled to make sure their contingent included women too.

Boss remembers that she and her counterpart, Tatiana Gurko, who were to write on a chapter on gender roles in marriage, had vastly different views of feminism—but as Boss learned, understanding someone’s context is everything. Gurko had grown up in a country where an entire generation of men had been decimated by WWII—men were a scarce commodity.

The following year, the eight FSOS faculty traveled to Russia for 10 days where they toured facilities, conducted open forums, and shared meals with their Russian counterparts. In addition to the 1994 book, Families Before and After Perestroika: Russian and U.S. Perspectives (co-edited by Maddock and Hogan), the exchange also opened opportunities for Russian students to pursue graduate degrees in Minnesota.

Hogan became the newly formed College of Human Ecology’s (CHE) associate dean in 1989. Olson served as interim until Harold G. Grotevant joined the department from the University of Texas, Austin, in 1990. While the need for research and outreach in service of families continued to grow, state financial support did not. Grotevant would have to guide the department through reductions and reallocations as state support of the U of M fell.

The 1990s – Achievements and Retrenchment

“It was a time of significant budget cuts,” says Grotevant. But he believed the University could transcend the financial challenges and that Family Social Science could help lead the way.

Grotevant looked for opportunities to build bridges with other departments and the University-Community Consortium on Children, Youth and Families, launched in the fall of 1991, was among the solutions.

“The consortium brought together faculty and resources who were all working to support children, youth, and families in one place,” says Grotevant. “It was a resource gateway for professionals, families, and individuals to connect and support each other and where faculty could share expertise.”

The consortium quickly grew and today it is housed in Extension where it still brings together researchers and practitioners to support families and communities throughout Minnesota.

Budget was not the only pressing challenge Grotevant addressed as department head.

“When I was hired, there was the marriage and family therapy program and then, everyone else,” he says. “There were great things going on and my question was—how can we elevate all of our research?”

Discussions, retreats, and “a lot of walking up and down McNeal’s hallways” built an FSOS framework for theory, research, and outreach around four broad areas:

Family economic well-being

Families and mental health

Family diversity

Relationships and family development across the lifespan

Despite budget cuts, in 1994 Family Social Science began a two-year celebration of the United Nation’s Year of the Child (1994) and the department’s 25th Anniversary (1995). The department welcomed national meetings of the American Council of Consumer Interests and NCFR as well as a major exhibit on families with the Minnesota Historical Society.

Grotevant would exchange roles with Hogan, who—following service as associate dean of CHE and a sabbatical—had returned to the FSOS faculty.

“We had such a great faculty and students,” says Hogan of her second time around as department head. “I look back and wonder how I did it, but I had such a great staff—the problem was the CHE dean kept stealing them!”

Hogan would continue to develop partnerships that attracted international graduate students from across the world while at home faculty were involved in diverse research, Extension, and outreach projects that included informing and advocating for family-friendly policies as financial issues continued to affect rural Minnesota.

Bauer’s research on welfare reform and rural families grew into the “Rural Families Speak” project, a research collaboration with over 50 faculty and Extension researchers from 17 states. Danes’ research into family businesses and how family dynamics impacted relationship satisfaction was also garnering attention, while Stum’s research-informed workbook, “Who Gets Grandma’s Yellow Pie Plate,” transformed how families coped with the transfer of non-monetary assets.

The department also welcomed new faculty members Carolyn Tubbs and Virginia Solis Zuiker, who would expand research into diverse families and their finances and the use of collaboration to improve clinical supervision processes. Martha Rueter’s research included a longitudinal study of rural families and would grow into adoptive families’ communication.

Turn of the century – Transitions and Tragedy

In late 2001, Grotevant and Hogan would exchange roles once more, with Grotevant serving a two-year interim term. Hogan would return to teaching and to a new research project, Family Assets for Independence in Minnesota (FAIM) that encouraged individuals to save by providing matching funds and money management classes.

The department also began to experience its own generational shift brought on by the retirement of Zimmerman in 2000 and Olson in 2001. Two incoming faculty members, William Turner and Elizabeth Wieling, would bring new diverse cultural and international perspectives to the FSOS department.

The excitement of the new academic year would be overshadowed by the national tragedy of 9/11. The attacks of September 11 would bring family social scientists into the heart of the national tragedy just days after the attacks. A team led by Boss that included Turner, Wieling, and graduate students would make three trips to New York City to help members of the service workers union and their families cope with the loss and trauma.

One of those graduate students was Tai Mendenhall, a doctoral student who would join the U’s family medicine faculty following graduation and eventually return to FSOS in 2007.

“It changed the trajectory of my career,” says Mendenhall. “It felt like we were learning to build the ship as we sailed it and I have carried those lessons forward throughout my entire career.”

As the University’s relationship with constituencies evolved, a model developed by Doherty began to be recognized for its innovative approach. Doherty’s civic engagement model emphasized collaboration with communities to determine problems to be addressed and action steps to be taken. Early projects included a series to improve the health and well-being of Native American families and organizing mentors to support teens managing diabetes.

Also bringing new research approaches to the department was Jodi Dworkin in fall 2002. Her research examined adolescent risk-taking behaviors as a normal part of identity formation instead of through a previous negative lens. As the use of texting and various communication apps increased, her research would expand into how teens and parents use these technologies—or not—to stay connected.

Family Social Science also continued to respond to technological changes with the development of online courses. Hogan was the FSOS trailblazer, teaching Personal and Family Finance spring semester 2003. Dworkin developed an online course on alcohol use by college students for parents later that year, and Solis Zuiker followed in 2004 with a class on responsible credit card use.

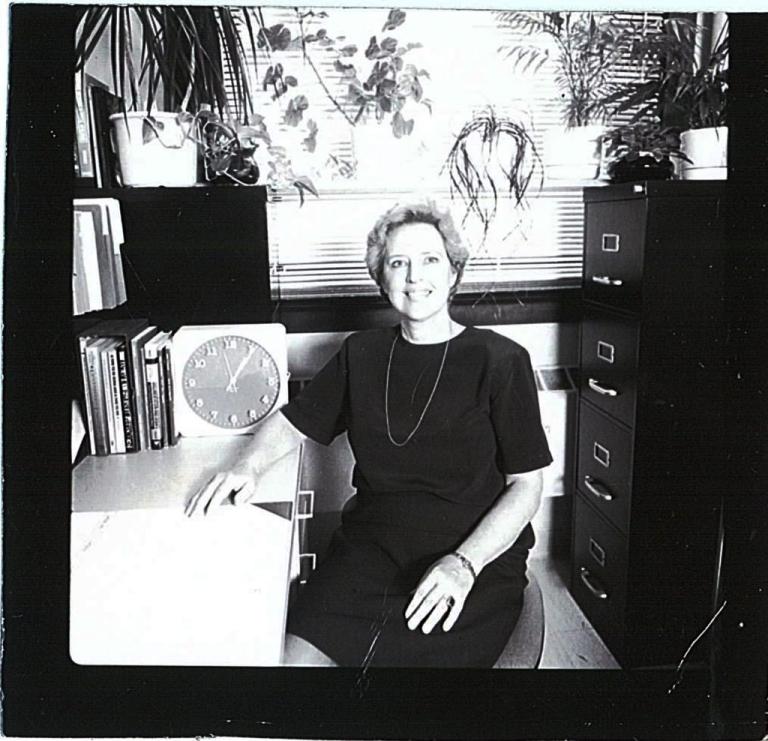

Jan McCulloch came to Minnesota from the University of Kentucky to lead the department in the summer of 2003.

“FSOS was considered the very best in the country,” says McCulloch. “Yes, it was a challenging time—budgets, integrating technology, and responding to diverse communities—but it was a department with a long legacy, and I felt we could incorporate those strengths with new strategies to accomplish our mission.”

McCulloch’s research had focused on aging in rural America and it was that ethos of strength and resilience that was the foundation of her people-centered leadership style.

“I really cared about people and wanted the department to be a good place to work,” says McCullough. “I was always proud of our commitment to diversity—in admissions, coursework, faculty/student interactions, and community collaborations.”

She also led the department through the difficult transition in 2006 as the College of Human Ecology was dissolved and Family Social Science was moved into the new College of Education and Human Development (CEHD) as part of a larger University strategic plan.

“It was a challenging time—to move from an intimate but intellectually diverse college to one that was diverse but focused on one large issue—education,” says McCulloch. Looking back, she reflected that change is never easy, however the department gained a very explicit focus on family education and the resources of a bigger unit.

The department gained new faculty members Beth Magistad, Sara Axtell, and Zha Blong Xiong through internal transfers that strengthened the focus on undergraduate success. The parent education programs would transfer from another CEHD department to FSOS and add Susan Walker to its faculty.

FSOS faculty also adapted their research agendas to support individuals and families in the changing American society. Following research that uncovered how uncertain some couples are about divorce, Doherty collaborated with a Minnesota legislator to pass a “Couples on the Brink” bill to improve counseling to couples seeking divorces. Steven Harris would join FSOS from Texas Tech to co-lead the project.

Responding to the needs of parents who were members of Minnesota’s National Guard, new faculty member Abigail Gewirtz launched the research project ADAPT (After Deployment, Adaptive Parenting Tools) to provide tools and resources to help families coping with the stress of deployment and reintegration. It would attract major Department of Defense support and national media.

The economic downturn of 2008 also saw FSOS faculty stepping up to share their research to help individuals and families cope. From sharing advice on talking to children about the economy to avoiding inheritance conflicts to pushing back on Black Friday—FSOS faculty members offered hope and evidence-based advice.

McCulloch would continue to develop the department’s focus on diverse families and attract diverse students in a variety of ways. Proactivity and celebrating accomplishments were a hallmark of McCulloch’s leadership and her communications always balanced challenges with words of encouragement.

“Without places like Family Social Science,” she wrote, “Stereotypical ideas and unfounded assumptions about families can continue to affect individuals and their families as well as local, state, and federal policy.”

McCulloch finished her term and stepped back to join the faculty in 2013 while Lynne Borden joined the University from the University of Arizona to head the department. She would bolster Couple and Family Therapy (CFT) faculty by adding Gerald August, Tabitha Grier-Reed, and Timothy Piehler via internal transfers and hiring Lindsey Weiler. She would also add Extension specialists Jenifer McGuire and Joyce Serido to address issues around LBGTQ youth and youth financial literacy, respectively. Heather Cline would join the faculty to teach in the parent education program while Margaret Kelly would join the faculty to become director of undergraduate studies.

Faculty in the department continued to pursue diverse research agendas and community collaborations to establish parent-education programs in Iceland, inform policymaking around social services for immigrant and refugee families, develop youth mentoring programs, and build financial literacy, among many others.

Borden would return to the FSOS faculty in 2018 while Dworkin stepped into an interim role for two years. Leading FSOS as the pandemic shut down face-to-face classes and curtailed research, Dworkin launched an internal grant program to support faculty/graduate student teams in studying the effects of the pandemic on individuals, couples, and families. She would also lead searches that brought Armeda Wojciak (CFT program director) and Chalandra Bryant (Pauline Boss Faculty Fellow in Ambiguous Loss) to the department.

Stacey Horn was named department head and began in August 2020. The U of M alumna returned to Minnesota from the University of Illinois at Chicago. She received a bachelor’s degree in child development and English from the U of M, a master’s in English from the University of St. Thomas, and a doctoral degree from the University of Maryland College Park.

A former high school English teacher, Horn’s current research focuses on prejudice related to sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as bias-motivated bullying among adolescents.

“I was excited to be coming back to my roots in a department with great faculty doing work that really contributes to the lives of Minnesotans,” Horn says. The pandemic and protests following George Floyd’s death heightened the sense of urgency around diversity, equity, and inclusion in how she approached her work in the department.

“Diversity, equity, and inclusion are core values of the department but that’s not enough—we have to push to the next level,” she says. She describes her approach as “liberatory”—harkening back to the writings of Frederic Douglass.

“We have to interrogate our practices and priorities and evolve to claim with certainty that we are an antiracist department,” she says. “Equity and inclusion are great but if there are ways that structures, policies, spaces, and interactions are impeding people, we’re not really progressing. We have to reduce systemic barriers and increase opportunities so everyone can realize their authentic potential.”

She noted that in the last 50 years, the very idea of families has changed. In conversations she has had with current faculty and staff, professor emeriti, alumni, and donors, Horn says their passion and commitment to FSOS is evident and learning how the department has responded to the needs of the time was clearly a point of pride. Horn believes that Family Social Science has a role to play in the larger agenda of the University of Minnesota and the state.

“I am looking forward to working with the FSOS community to envision a future that doesn’t even exist yet and determining our place in it,” she says. She adds she is especially looking forward to being back on campus and working with colleagues in person.

“Being on the St. Paul campus and hearing the backstory on McNeal Hall and its place in UMN history was amazing,” says Horn. She admits that driving through the U of M’s main gate in Minneapolis was a particularly emotional moment.

“FSOS has been such a leader in shaping the field of family studies and has been home to some of the most outstanding scholars, leaders, and teachers nationally and globally,” she says. “I hope to do justice to the rich legacy of this department and the remarkable people who have made it what it is, so that FSOS is successful for the next 50 years!”

Photos courtesy of the Department of Family Social Science

-Julie Michener